The Religious Science of Johns Hopkins: Spiritual Direction

The varieties of psychedelic mysticism driving a psychedelic clergy study. Part two.

This is the second part of a series detailing spiritual missions, hidden issues, and unexamined consequences of a psychedelic clergy study. Each day this week, I will share a new piece on a different part of its story.

In part one, I laid out a high-level view of what I came to see as a disturbing picture of psychedelic research on religious professionals. In this piece, I will dive more into the specifics of the spiritual beliefs and cultural agendas of researchers that are in the public record.

It seems the Hopkins psilocybin experience is the artifact not only of this powerful molecule, but also of the preparation and expectations of the volunteer, the skills and worldviews of the sitters, Bill Richards’s flight instructions, the decor of the room, the inward focus encouraged by the eyeshades and the music (and the music itself, much of which to my ears sounds notably religious), and, though they might not be pleased to hear it, the minds of the designers of the experiments.

Michael Pollan, How to Change Your Mind, 20181

Rick Doblin, the head of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelics Studies (MAPS), loves to describe two of his main goals as “net zero trauma” and creating a “spiritualized humanity,” From a strategy perspective, he has described what MAPS does as “political science” — that is, science designed to persuade politics towards these spiritual ends. In this regard, Doblin has been remarkably successful.

And he is far from alone in his spiritual vision, or success in gaining institutional favor. The core Hopkins psilocybin team behind the religious professionals study, along with NYU’s joint investigator, have discussed their own spiritual and religious beliefs in psychedelics for many years. In this piece, I will explore some of these beliefs and examine whether their research goals have included a strategy to advance those beliefs.

During my involvement in a participant’s non-profit, not only was I aware of the history of psychedelic religious positions various psychedelic researchers held, I once held them myself quite passionately. They gave me tremendous hope and meaning in the midst of an otherwise materialist view of the world. As I adopted their beliefs through reading their books, attending their conferences, and listening to their interviews, I found them to have a perfect internally-consistent logic: scientific, yet more-than, universal and deeply compassionate, just making a satisfying amount of sense. Like many, I shared the core psychonaut belief in “no dogma,” seeing it as the source of so much of the world’s pain and suffering, the source of so many religious wars. I came to find that in the case of psychedelic religious science, there is hidden doctrine within the “doctrine of no doctrine” — but that isn’t, itself, intrinsically a bad thing.

Leaders of the Hopkins arm of the religious leaders study include the original Hopkins psilocybin research team: Dr. Roland Griffiths, Dr. William Richards, and advisor Bob Jesse, as well as Dr. Anthony Bossis leading the NYU branch of the trial. The Hopkins team has been famous within the small field since their landmark “mystical-type experiences” study in 2006, celebrated by many psychedelic actors as opening doors and funding for psychedelic research.

Each also has longstanding ties to MAPS, which has pursued what some have described as a “Trojan Horse” strategy. As Michael Pollan has described Rick Doblin, Doblin sees the medical use of psychedelics as “a means to a more ambitious and still more controversial end: the incorporation of psychedelics into American society and culture, not just medicine.”2

Doblin repeatedly emphasizes that one of the impacts of a “spiritualized humanity” will include a world of “net zero trauma,” sometimes attaching specific years to his aims. I genuinely do not know how this is calculated, but in 2021, he seemed to change his mind about whether “net zero trauma” would be by 2050 or 2070.

RiverStyx, a primary funder of the religious professionals study, has funded MAPS $3.8M since 2009, with RiverStyx co-director Miriam Volat sitting on the Board of Directors of MAPS’ Public Benefit Corporation. RiverStyx’s other co-director, T. Cody Swift, was part of the religious professionals research team, interviewing all participants alongside another interviewer, and later as part of the team analyzing the data.

When I first heard about the study as a psychedelicist, I was excited, even if the science was practically a formality to prove what we all already knew, and we knew it because we had experienced it directly.

In an interview last year, Dr. Griffiths said, “Although this is not about changing culture, it has implications for cultural change, but we were not trying to turn people into evangelical psychedelic proponents. I don’t think any of the investigators wanted that.” It might be true that none of the researchers wanted to specifically create “evangelical psychedelic proponents.” But there’s a lot of other ways to change culture besides trying to create “evangelical psychedelic proponents.” Based on my experience working in the non-profit, which I will talk about in a future post, and when one looks at their extensive publicly attested beliefs with a discerning eye, including in Michael Pollan’s best-seller How to Change Your Mind, it is hard to conclude that the religious leaders study was not primarily part of a strategy to integrate psychedelics into mainstream religion. At least, that’s what I thought I was working for.

The Experiential Doctrine of Bob Jesse

Bob Jesse may not be the lead author of the study, but his organization is its sponsor, and you cannot understand Hopkins’ research without understanding his influential role in marrying science with psychedelic spirituality. Jesse’s ability to bring Dr. Richards and Dr. Griffiths together to Hopkins more than twenty years ago proved to be a landmark pairing that the current wave of psychedelic research is indebted to.

In an extensive profile for Michael Pollan’s book, Pollan remarks that Jesse is on a “mission” to revive psychedelics, “not so much of medicine as of spiritual development.”3 He has been a kind of guide-of-guides in navigating what has always been a political project, carefully thinking about cultural sensitivities to address. Pollan has also described Jesse as a primary leader of the strategic vision of psychedelic research ever since his involvement in Bay Area psychedelic strategy meetings since the 1990s,4 convening and maintaining the Council on Spiritual Practices (CSP) since 1995. The CSP is the sponsor of the religious professionals study.

Jesse has been interested in developing a stronger religious foundation for psychedelic work, from what seems like a sincere, heartfelt place to help the world spiritually flourish out of its modern malaise. Rather than diametrically opposed to mainstream religion, he has attempted to persuade psychonauts that the “r-word” of religion need not be so scary.

Before the religious professionals study began in 2015, he gave a lecture at the 2013 MAPS Psychedelic Science conference called “From the Johns Hopkins Psilocybin Findings to the Reconstruction of Religion.” In the talk, Jesse described the martial art Aikido—not to “oppose” something, but about peace, love, and non-harmfulness, to “blend” with it to “take it in a safe direction.”5 “I’m not gonna say exactly how I think it relates to this,” he said, “except that I’m pretty sure that it does…We’re learning to do religion better.” He also described the mystical experience (induced by psychedelics or other means) as introducing a new “doctrine” that can impact the other doctrines of one’s religion,6 and in a 2016 talk, that he sees a psychedelically-induced mystical experience as a “birthright”7

In extended remarks for a 2021 meeting with the Boston Psychedelic Research Group, Jesse spoke of the origins of his psychedelic involvement at the Esalen Institute in the 1990s. He mentioned that the very earliest psychedelic strategy conversations he was involved in focused on the question, “What would it take to draw attention to these materials for their sacramental potential - not only their healing potential?”8 They concluded that part of this would involve finding a scientist to conduct psychedelic research at a top university, with a pristine reputation, on “healthy normals.” While perhaps these moves appear cynical now to some, perhaps it was because they were in the context of draconian drug policies and cultural attitudes against drug spirituality.

I still have sympathy for his perspective and appreciation for his predicament. I only recently discovered that he frequently cites Harvard ‘60s unsung hero Licia Kuenning (known then as Lisa Bieberman) as a source of inspiration, who is also a source of my inspiration. And it must be said that Jesse has also consistently expressed greater caution than the rest of the psychedelic movement. Like many, I had an appreciation for his more measured approach among accelerating enthusiasm.

From his old lectures before much-smaller psychedelic audiences, it seems likely to me he anticipated a longer timeline of psychedelic cultural acceleration than what this study turned out to coincide with. He has often seemed more realistic about the timeline of healthy psychedelic integration into Western religion as taking many generations, and encouraged others to call out the mistakes as part of that process. If he thought that psychedelic mystical experiences were “a kind of doctrine,” he also hoped that "the mystical experience gives you a chance to make a sanity check on your [other] doctrine.”9 But I have to admit that while I think he genuinely respects religion, I don’t think this approach really respects science.

The Secular Spirituality of Roland Griffiths

According to Michael Pollan, Jesse’s “campaign” was “a master plan in which Dr. Roland Griffiths plays a central role.”10

Dr. Griffiths has spoken extensively about his ideas around consciousness and “mystical-type” experiences. While in December 2022 he called his colleague Dr. Richards a “true believer” in psilocybin research,11 Dr. Griffiths has his own strong views that psychedelics will be a key to saving humanity. He still holds some of his views close to the vest, as well as personal disclosures of his own experiences. Former Hopkins researcher Katherine MacLean, PhD, described Dr. Griffiths as emphasizing to the team over a decade ago to not disclose their personal drug use, which to be fair, makes it little different than most other American workplaces.12

In the wake of a Stage IV colon cancer diagnosis, Dr. Griffiths recently established a professorship studying "secular spirituality”, a view he described in May as “stripping away from spirituality any need for supernatural ideas or beliefs or theological beliefs but embracing the idea that we're living within this benevolent mystery and it's currently unsolvable, and there's something incredibly uplifting.”13 This perspective spoke to me when I was in the throes of my psychonaut explorations as a New Age-adjacent Californian. If the psychedelic journey was less about beliefs and more like music, psychedelic science could be used to learn how to better chart its theory so more people could play it. I was confident that my psychedelic secuarlity lived outside the realm of belief. We just lived in reality as it is, and psychedelic mysticism is merely a part of that reality.

However, many philosophers and religious scholars argue that secularity cannot be seen as simplistically as an absence of belief.14 The Hopkins study team itself is split on this; Rachael Petersen, qualitatitive analyst for the religious professionals study, also questioned this in late 2022, saying that “what gets labeled as ‘secular’ is often much less so than it seems.”15 This challenge to secular neutrality was a pivotal part of a piece describing a harrowing experience when she was originally a Hopkins research subject.

An example of one such “secular spiritual” belief is the belief that psychedelics carry intrinsic spiritual value, often tied to their ability to invoke meaning. Alongside Hopkins psychedelic colleague Dr. David Yaden, Dr. Griffiths has argued that even if a safer kind of psychedelic were developed with no psychoactive effects (as in “without the trip”), the “meaningful” quality of classic psychedelics would still make them the more ethical default option.16 This position has received criticism from other bioethicists,17 who argue that “meaningfulness” is out of the “proper scope” of medicine and “non-relevant” to the immediate concern of clinical outcomes.18

This is not outside of Dr. Griffiths’ scope; Dr. Griffiths has long touted Hopkins’ results as reliably producing psilocybin experiences in patients that rival importance to the birth of their child. To Dr. Griffiths, and many other psychedelicists, this is a major spiritual green flag. To others, it is a spiritual red flag—do psychedelics distort our relationship to what is healthy, proper meaning? Should a drug experience feel as important as the birth of one’s child? Or is this a signal that something has gone wrong on a spiritual level beyond experiential bliss? This, itself is an “ought” question that can only be answered by one’s beliefs, but Dr. Griffiths has advanced this meaning-making (if not meaning-simulating) property as if it is belief-free.

Writer Ed Prideaux, who has led research into the psychedelic side-effect Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) after experiencing HPPD himself, has wondered whether psychedelics are deeply meaningful or whether they seem to merely mimic meaning. As Prideaux argued in an email:

The psychedelic state and its ready-and-fast pump of meaning provide an ideal recipe for an unethical inflation of meaning beyond the facts. Consider those who keep going back to its well for a ‘meaning high,’ or the subtle ways that one’s psychedelic enthusiasm can become obsessive and colonial of one’s attention… Witnessing the birth of a child is meaningful and should be meaningful. It is serious business for an effect produced by a psycho-technology, scaled and under the control of pharmaceutical corporations, to compete with such an event at all.

To build on what Prideaux is saying here, meaning cannot exist in a vacuum. The very fact that compounds simulate meaning tied to experiences driven by compounds potentially creates a closed-circuit loop of meaning, as in, “psychedelics are meaningful because they generate meaning.”

There are real trade-offs to think about here. While many psychedelic medicalization advocates champion the cause of having a safe setting with a strong intention, and for good reason, it remains an open but serious question if a recreational approach may actually be safer in some respects. It’s something I first heard long-time psychedelic journalist James Kent ask as part of DoseNation, a long series exposing memory-holed psychedelic history. In 2016, Kent wondered if it was at least possible that taking psychedelics in a recreational setting might actually be mentally safer in some respects than in guided psychedelic therapy, even if in other respects it has different risks. The theory is because if psychedelics can significantly dial up the salience on anything in your consciousness, that effect may be heightened when one goes in with the intention to have a religious experience or therapeutic insight. In a setting like Burning Man, where you may just want to have a fun sense of recreational spirituality, Kent argued you are more likely to write off harmful or false insights as just the drugs talking. And in my experience, there may be some truth to this—while recreational settings have their own real safety issues, I never changed my religion after a Phish show (I was Already There).

Whether one shares Dr. Griffiths’ secular spiritual psychedelic meaning, or is interested in psychedelics just for the party, I think anyone’s positions about psychedelics and spirituality are inherently theological. In my experience as a spiritual seeker, when we believe we have the “dogma of no dogma,” it just means our real dogma is unconscious to ourselves.

The Perennial Mystery of Anthony Bossis

While Dr. Griffiths’ “secular spirituality” seems to make a claim about neutrality through being devoid of belief, there’s an opposite way to claim neutrality: psychedelic religious universalism.

An older, popular psychedelic theology is sometimes known as the “perennial philosophy,” a view grounded in neo-Platonism and advanced by Aldous Huxley. At its core is an Abraham Maslow quote Dr. Anthony Bossis used during the study presentation: “All religions are the same in their essence and have always been the same.” But what is that essence? How are they all the same?

It appears to be a belief in a “core mystical experience” that is “universal to all religions.” In this theology, psychedelics are just one of many practices in which one can alter consciousness to find the core of religious essence. But despite this psychedelic theology’s claim to universality—the unabashedly religious flip-side to Dr. Griffiths’ universal secular spirituality—its claims about mysticism are far from held by all mystics nor scholars of mysticism, as religious professionals study team member Petersen pointed out back in 2019.

In one interview, Dr. Bossis appears to have described religiously-oriented goals for his psychedelic studies based on the Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece, a mystery cult that likely used psychoactive substances for religious purposes. In interviews conducted for Brian Muraresku’s 2020 book The Immortality Key, Muraresku describes Dr. Bossis in the following way:

From what I’ve picked up from Anthony Bossis in recent years, a more responsible [psychedelic] movement is afoot. Something that could truly speak to the practical mystics by the tens of millions in this country, and eventually hundreds of millions around the world. Something that has been many thousands of years in the making…The whole point of these psilocybin interventions, [Bossis] concedes, is to trigger the same beatific vision that was reported at Eleusis for millennia.19

If Muraresku is conveying Dr. Bossis’ views accurately, did participants know that this was the whole point? That, if the above is true, they were sought in an experiment to “trigger the same beatific vision” of this ancient mystery cult?

Again, I think there is hidden dogma afoot even when it appears absent. Again, I don’t think dogma is intrinsically bad. But the hidden dogma in much of psychedelics is centered on the primary importance of one’s consciousness. The perennial “mystic” philosophy asserts that the core of religious truth is derived from experiences plunging the depths of human interiority. But this is not actually universal to religion, not even universal among religious traditions who highly value inner transcendent experience. And it has real theological consequences: to center a subject’s consciousness is to center one’s meaning in one’s self, and this posture can become especially prone to narcissism, both personal narcissism and of a subculture’s collective narcissism.

The perennial philosophy’s hope is that in the absence of any particular religion making any sense whatsoever, one might find something universally true in exploring our consciousness to its depths. If this is what Dr. Bossis holds, it is similar to the last primary Hopkins figure I’ll explore, Dr. Bill Richards.

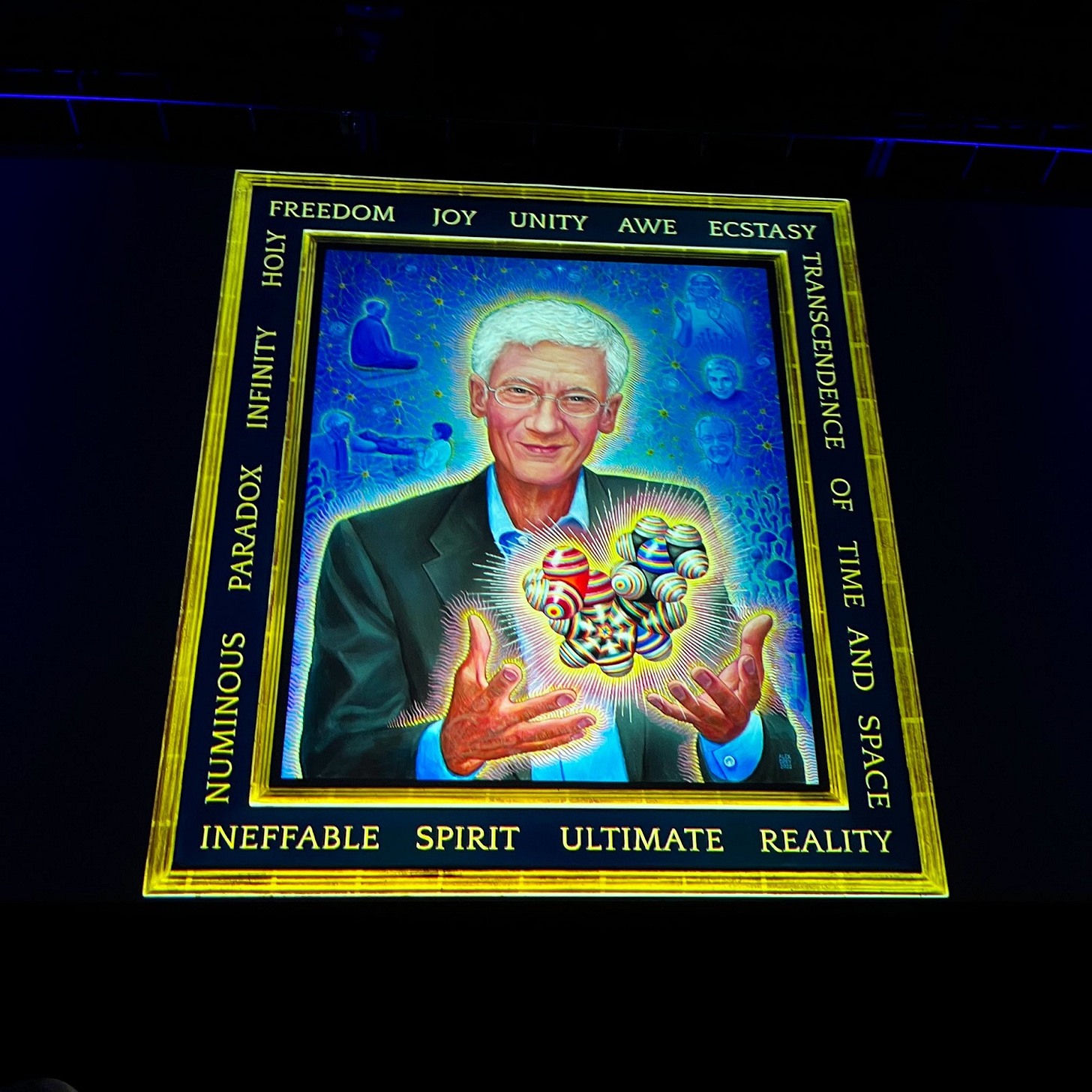

The Universal Consciousness of Bill Richards

Dr. Richards has been described affectionately as a sweet grandfatherly figure, the “mystical mind” of the Hopkins program.20 Proudly in the perennial philosophy tradition, Dr. Richards is among the oldest psychedelic researchers still active, having played a role in 1960s and 1970s research (Walter Pahnke, who led the famous Good Friday Experiment that inspired this religious leaders study, was the best man at his wedding). His sincere passion for psychedelic mysticism only got mocked at Yale Divinity School in the 60s, but he has finally gotten a long-awaited last laugh over the religious scholar critics.

Dr. Richards, like many of his subjects, had his first psychedelic experience as a volunteer research subject. According to Michael Pollan, he has “three unshakeable convictions”:

The first is that the experience of the sacred reported both by the great mystics and by people on high-dose psychedelic journeys is the same experience and is “real”...Second, that, whether occasioned by drugs or other means, these experiences of mystical consciousness are in all likelihood the primal basis of religion. (Partly for this reason Richards believes that psychedelics should be part of a divinity student’s education.) And third, that consciousness is a property of the universe, not brains.21

I didn’t read Dr. Richards’ book until earlier this year, but we shared a great deal in common in our orientation. To the extent that I felt like I had a precious gift that was poorly understood, but I wanted to be widely shared, I can only imagine what it was like for Dr. Richards to hold onto his convictions throughout the cultural climate of the 70s, 80s, 90s, and on.

Dr. Richards’ 2015 book serves as a treatise on his personal beliefs about psychedelics and religion that span back to his involvement in early psychedelic research. The book has drawn criticism from researchers like Rick Strassman, PhD, who has argued Richards’ book is part of an attempt at "creating his new religion.” In his review in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies in 2018, Strassman even raised concerns directly about the religious professionals study:

It is in this light that one should retain a healthy skepticism for the “religious leaders” studies now occurring at New York University and Hopkins…It is inevitable that researchers will use these data to support their notion of a “universal, core, primary mystical experience” underlying all particular faiths.

Strassman did note that “Richards’ religious model ought not to call into question the efficacy of the protocol devolving from it,” indicating there may be therapeutic utility that might be extracted from its religious nature.

Dr. Richards has commented in recent years that he hoped religious institutions would become “emboldened” to embrace psychedelics, with a strong desire to see legal clinical psychedelic usage in his lifetime. And as someone who once deeply shared this hope, I understand the desire to psychedelicize traditional Christianity. After all, to spiritual-but-not-religious people, modern Christianity can often feel at best like a disenchanted mishmash of dying institutions divorced from the experiential needs of people living in what has been called “meaning crisis.” Dr. Richards’ patience in his convictions had paid off: mainstream religion is finally getting closer to understanding, and he was blessed enough to be able to legally guide religious clergy, a once-in-a-generation opportunity to usher the next generation into a better world.

Clouds and Complications

With these backgrounds outlined, there is still foggy obscurity around the conscious intentions of researchers involved and what might have been unconscious. While it can be assumed they all wanted the study to have good results, it also seems clear that each might have had different specific desires for the study outcome that might have come into conflict. And they might have changed significantly from its start in 2015 to the dramatically different public environment in 2023. But it is really, really hard for me to take Dr. Griffiths seriously when he says that “this [was] not about changing culture.” It asks the listener to suspend their critical thought, to choose to believe these words this time but not other words from the team at other times. That doesn’t mean they all specifically wanted to create ambassadors for their views…but it happened, and with no small encouragement from a funder and member of the study team.

In contrast to Dr. Griffiths’ assertion last year that the study “is not about changing culture,” RiverStyx, who funded the study, seems to see their role differently. Their funding priorities, per their website, is:

Preference to early-stage projects and emergent paradigms with the potential to deliver innovative models, tools, and policy for social transformation…We seek high-leverage social change by providing resources to fringe areas that have been most stigmatized and disregarded by society and the funding community, in hopes of effectuating enduring change in both cultural awareness and social policy.

But even if I think the study was quite obviously about changing culture, this doesn’t mean they wanted everyone to trip. In his 2013 talk to a MAPS conference, Jesse expresses a careful, limited psychedelic vision that does not seek to make everyone a psychonaut, but does seek to impact religion by introducing psychedelics into it, and vice-versa:

“We’re learning to do religion better….the most important thing to remember about doing it better is ‘direct experience’ keeps it vital, ‘tempered through community’ is what keeps it from going off in weird unserviceable directions.”

This “direct experience” is the core of psychonaut thought, and what Jesse would say offered:

“a new perspective on ultimate reality [that] is the first little bit of doctrine. ‘Wow things are more connected than I thought they were’ - that's a doctrine. Something you now think is true about the world. that's one of the pillars of religion.”

In my opinion, it appears Jesse wanted to introduce this new “pillar” to existing religious traditions to avoid the pitfalls of “new [psychedelic] groups” that, despite their freedom, can be more shallow and less stable. The theology of the mystical experience itself may be universal in its vitality and potential to work with religions, but that does not mean he wants all to trip: “When I think about what it takes to generate a planet with more happiness…it will take structures and communities with mystical experience…there need to be communities, not dosing the water supply.”

Rather than wanting to outright dose the world, Jesse has discussed in the mid-90s a trepidation around opening a cultural Pandora’s box. In spite of the hesitance of his late mentor, religious scholar Huston Smith, they figured it would be opened eventually anyway. So, according to his 2021 reflections on the early years of psychedelic strategizing at Esalen in 1996, “The question before the group was, ‘We all think there’s a role for psychedelics. We all believe…the world might be ‘undersupplied’ with mystical-type experience, direct experience of the sacred. Which doesn’t mean to increase the supply willy-nilly. But on population, if more people had that kind of insight experience, it might on average be good for the world.” Per Jesse, “as if planning strategy for a business,” they came up with three items: developing a code of ethics, finding a legal case for religious freedom, and scientific research with a pristine reputation.

I find myself wondering, how do we make sense of Jesse’s openness about Hopkins’ psychedelic research being part of a nearly thirty-year strategy to advance spiritual interests through science? If they didn’t want to change culture, what did they want to happen?

Again, it’s complicated: Jesse has expressed a concern around promotion and things progressing too quickly. In a 2017 conference talk given in his genre of psychedelic states of the union, Jesse feared the movement would be derailed by immaturity:

So what could go off track? When there’s a lack of skilled, experienced, and networked leadership, people can get hurt; there can be medical emergencies, lasting psychological harms; and there can be more subtle issues that I’ll talk about later…So much of what we call “immature religion” comes from unwholesome or confused motives, and from leaders overestimating their readiness to lead. The problems often emerge around money, sex, holding what you might call “the chalice of revelation” or other power issues.22

It’s a quote that is more apt for the study than may initially appear. And it does suggest that the religious professionals study wasn’t trying to create psychedelic evangelists, per se. This is especially because if there is another feared foe alongside Dogma to the psychedelic movement, it is his brother Backlash: the fear that cultural attitudes could shift and shut down psychedelic research back into another dark age.

But is a long-term psychedelic strategy to advance psychedelic spirituality an appropriate use of science? More basically, is this good science? While I was once an active proselytizer of psychedelic public relations, I began to wonder, was it ethical to advance our spirituality through scientific PR soundbites? Even with how bad public opinion used to be about psychedelics, other groups had secured their legal religious freedoms through the Supreme Court (including with help from Bob Jesse), and more were still earnestly trying—why not channel more energy into that more honest strategy?

And in this study, were the study participants aware of what they were recruited into? I also began wondering about its implications on other psychedelic research. How much was motivated by religious and spiritual beliefs?

So What?

Maybe some are still asking: so what? Didn’t Michael Pollan already cover this? Aren’t researchers allowed to have personal beliefs? Can’t their research be related to those beliefs? Yes, of course they are (and do). Is there anything intrinsically wrong with their beliefs? Even though I don’t hold them anymore, I still believe in religious freedom. But if the study was overtly part of a broader public relations campaign for spirituality, is that an acceptable use of science?

This is a point where I am going to need more help from professionals in the psychiatric field as to the rules of the game here. I found a 2006 Resource Document from the American Psychiatric Association’s Corresponding Committee on Religion, Spirituality and Psychiatry, which stated, “Clinicians should not force a specific religious/spiritual, antireligious/spiritual, or other ideological agenda on patients or work to see that patients adopt such an agenda.” But that’s 2006 from just one APA committee, and I’m not a psychiatric researcher anyway—what are the binding guidelines here in 2023? I don’t know.

It may be that the views of the researchers above don’t sound that offensive or incompatible to existing theological views of traditional theists. And to some, they aren’t. But in the psychedelic 1960s, some Christian mystics were already concerned that the word “mysticism” was being misused for something with an entirely different relationship to God than tradition taught.

Thomas Merton, a monk devoted to reaching across religious difference and Eastern spirituality, had sympathies for the psychedelic movement, but also concerns that consciousness-based technologies aren’t just easily slotted in and out with Christianity—that it’s introducing a fundamentally different approach to faith. And it seems from these public comments that the researchers’ views are all consciousness-based, not theistically based. As Merton said in a 1967 circulation:

This use of drugs to “transform the consciousness” is now no longer in the stage of mere experimentation…We must realize that, underlying these experiments, is an essentially materialistic conception of man and human consciousness, which is nothing more than an emanation of matter. Since (in this view) even the highest and most “spiritual” experience of the human mind is in the end merely matter realizing itself in man’s consciousness, there is logically no reason why material aids (drugs) should not be used to make this realization more rapid and more effective. It is quite understandable that unbelievers should accept this view.

But it is disturbing to see Christians and Jews accepting it uncritically and, one might add, very naively, without apparently reflecting on the momentous theological implications of their act in regard to faith, grace, the love of God, and the awareness of our fallen situation in a world where matter can be turned against us by invisible adversaries.23

The researchers had psychedelic beliefs that were different from their subjects. And that’s okay. But if Dr. Griffiths says investigators “were not trying to turn people into evangelical psychedelic proponents,” they seemed to do more to enable it than discourage it. I knew that through my participation in a non-profit birthed from the study, funded by one of the study’s funders and researchers, a non-profit whose early goals were heavily focused on psychedelic PR for the study.

What I didn’t know, but what I would come to find out through researching Hopkins’ safety documents, was that the study team knew psychedelics lead to enhanced openness to suggestibility as early as 2008. And I learned that this suggestibility has been demonstrated to have impacted other Hopkins psychedelic research. And I learned the concern about psychedelics leading to unethical belief changes and guru complexes was raised by another Hopkins psychedelic researcher in 2021. And that will be covered in the next piece.

Part three can be read here.

Michael Pollan, How to Change Your Mind, 64.

Pollan, 36.

Pollan, 34.

Pollan, 37.

Robert Jesse, “From the Johns Hopkins Psilocybin Findings to the Reconstruction of Religion,” Presentation at MAPS Psychedelic Science 2013, youtube.com/watch?v=lM-yinhpOgQ, timestamp 33:00.

See note 5, timestamp 17:00.

Robert Jesse, “Psychedelic Renaissance,” Presentation at Horizons 2016, youtube.com/watch?v=2Ao88YbX2Zc, timestamp 7:11.

Robert Jesse, remarks for Boston Psychedelic Research Group, Jan 10, 2021, youtube.com/watch?v=LU1Aunh8EEk, timestamp 36:42 - 39:10

See note 5, timestamp 18:50.

Pollan, 38.

“The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts: Roland Griffiths, PhD,” https://tim.blog/2022/12/10/roland-griffiths-transcript/

Katherine MacLean, Midnight Water, Kindle edition, Loc 1254 of 4691.

Sunstone Therapies, “We Share the Cancer: Roland Griffiths and his wife, Marla, sit with Manish Agrawal to discuss how a stage IV cancer diagnosis has changed their lives,” sunstonetherapies.com/n-interview/transcript.html.

Most famously, see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age.

Rachael Petersen, “A Theological Reckoning with ‘Bad Trips,’” Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Autumn/Winter 2022. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/a-theological-reckoning-with-bad-trips/

David Yaden, Brian Earp, and Roland Griffiths, “Ethical Issues Regarding Non-Subjective Psychedelics as Standard of Care,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 31. 10.1017/S096318012200007X/

Katherine Cheung et al., “Psychedelics, Meaningfulness, and the ‘Proper Scope’ of Medicine: Continuing the Conversation,” in Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 2023.

Rasmussen K, Olson DE. “Psychedelics as Standard of Care? Many Questions Remain.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2022 Oct; 31(4):477–81.; Peterson A, Sisti D. “Skip the Trip? Five Arguments on the Use of Nonhallucinogenic Psychedelics in Psychiatry.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2022 Oct;31(4):472–6.

Muraresku, 388.

Katherin MacLean, Midnight Water, Kindle Edition, Loc 1323.

Pollan, 55.

Robert Jesse, “Psychedelics - Uncertain Paths from Re-emergence to Renaissances,” youtube.com/watch?v=skE-6Upg1ok, timestamp 6:30.

Thomas Merton, Notes on “Psychedelic ‘Spirituality’” For Collectanea Cisterciensia