The Religious Science of Johns Hopkins: The Silence and the Smile

Breaking the Code. Part five in a series about a psychedelic clergy study.

This is part five of a series detailing spiritual missions, hidden issues, and unexamined consequences of a psychedelic clergy study at Johns Hopkins University.

In part one, I gave my “high-level findings.” In parts two and three, I provided some groundwork for the spiritual missions of the Hopkins team and what are some heightened ethical concerns for high-suggestibility drugs and belief transmission. In part four, I talked about the reckless origins of the Christian non-profit I worked for, funded by a Hopkins funder-researcher and with a Hopkins researcher on its board.

Today, I will share where things went wrong.

Tomorrow, I will share how things have always been wrong.

Halftime

I would like to take a brief interlude for those who have followed the plot from part one. I’ve often felt in the past year and a half like I’ve been going through hell. Whistleblowers never get any practice at it; you pretty much get one shot, and you have to err on the side of less is more, like you are trying to put together a 1000-piece puzzle, but you only get to use maybe 400 pieces to show the picture. Part of that hell is having my hands tied from what I wish I could say.

Until we’re on the other side, all I can do is remix a Winston Churchill phrase: if the road to hell is paved with good intentions, then all I can do is have the best intentions to keep going. But there is another side.

True silence has a holiness that should always be kept sacred. Some silences don’t deserve to share the honor. This includes The Silence.

Open Secrets

It’s not just hell’s road—everyone has noble intentions. This includes Ligare, the Christian non-profit I worked for, whose origins I discussed last piece.

It did not take long into Ligare’s origins for the organization to begin questionable practices. What I can say is that according to my conversations with multiple Ligare board members, the Rev. Priest facilitated illegal psychedelic ceremonies with the knowledge of members of the Hopkins study team, again, while being funded by a Hopkins researcher.1 Ligare also began directing people to unregulated psychedelic practitioners; while working for Ligare, I personally referred one inquirer. But honestly, this kind of thing is just part and parcel with working in psychedelics, a pretty open secret, yet while also pretending only to promote legal settings—marketed as reliably providing an encounter with the divine.

I terminated my internship early with Ligare in April 2022 with a letter to the Board, and later, to the other study participants I had met. As part of that, I began raising concerns about the conflicts of interest with the study team.

But I didn’t say the primary reason I left, which was due to disturbing conversations with several members of Ligare’s leadership team dismissing concerns of sexual abuse in psychedelic clinical trials. My other chief reason for leaving was Ligare’s refusal to prioritize offering their audience of average Christians—the recipients of their ambassadorship “education”—basic information about the risks of psychedelic use. As of today, two years after their launch, their website has nothing about it. Shortly after my resignation letter, Rachael Petersen stepped down from the Board.

Disillusionment

The real beginning of the end for me, my involvement, and any illusions I had that anything would be the same was when the investigative podcast Cover Story: Power Trip was released by New York Magazine, produced by Lily Kay Ross and David Nickles, two people who had been in a small professional psychedelic field for at least a decade. The focus of the podcast was on sexual assault, abuse, data issues, and more in a MAPS MDMA clinical trial, including abuse caught on camera, as well as an uncomfortable walk through the park of psychedelic history that you don’t get at a MAPS conference.

But like many psychonauts, at first, I didn’t want to feel the implications of what I was hearing. For its first half released in late 2021, I was mostly in denial of their disturbing descriptions of psychedelic history as an insular community whose penchant for breaking traditional norms sometimes meant the traditional norms of human dignity. I enjoyed my perch and social standing, and told myself the things people who don’t want to lose their place in a Movement tell themselves: “they just have an axe to grind; they’re just crazy; they’re well-intentioned but their points didn’t actually demand change—maybe they just needed more healing. In fact, MAPS is the real victim, not their victims.”

But as more of Power Trip emerged in early 2022, focusing on the sexual abuse of a MAPS clinical trial participant, my heart sank so hard it managed to bypass my cognitive dissonance. It broke my closed circuit loop of feeling psychedelics were so meaningful to the future of the human race because they feel meaningful. Maybe other things were more meaningful.

I immediately circulated the story to the Rev. Priest and a board member. I told them in an email we “couldn’t ignore” it; it was a story quickly spreading in psychedelic whisper circles, and the events the podcast were covering were quite severe. Maybe other scientists might find it too scary to jeopardize their careers, but we couldn’t stay in The Silence.

During this time, the Rev. Priest and I had a weekly standing Zoom call. I’ll never forget our chat when news of the abuse broke. His immediate reaction over the laptop screen was agreeing it was awful, before adding with a chuckle, “I’m just glad that happened before we got here, so we don’t have to get involved.”

At first, I became alarmed, hoping that it was gallows humor. There was more truth in the gallows than I knew. I felt heartbroken and betrayed—this response is simply not a Christianity worth believing in. Christians are called to get involved when people have been hurt, especially by powerful institutions, especially ones we have proximity to, and had those connections to. Rick Doblin was a phone call away for Hunt. We’re just glad it’s not our problem? This is psychedelic Christianity? Week after week my disgust and insistence on doing something more became more uncomfortable between us. Once, in response to my anger about the issues, he asked me in a sincerely concerned voice how long it had been since I had a good mushroom retreat.

On balance, perhaps Ligare should not be singled out for having a non-reaction to Cover Story. Most of the psychedelic research world still has said nothing. Maybe it’s status anxiety, maybe it’s conflict avoidance, maybe it’s too deep in the cognitive dissonance. Our pride is the last to believe we were manipulated for someone else’s utopia that doesn’t necessarily include a truly free version of ourselves. That’s obvious enough when you find your voice has been bought out, unable to speak against The Silence.

But perhaps instead of psychedelic exceptionalism, it was my Christian exceptionalism that made me think we would be any better in our response, a naive view in its own right given the history of abuse in Christian churches. And we certainly were not exceptional—the vast majority of psychonauts dismissed it and suppressed it. Nobody wanted to cut ties with MAPS, and Ligare ended up well represented at this past June’s MAPS Conference, alongside every other Christian psychedelic professional who never broke The Silence. They were rewarded for it.

But it’s also hard to know—was The Silence so dominant in Ligare because of the psychedelic culture, or just the study culture? I started trying to figure out why. And to this point, we haven’t really touched the most central entity to this story besides Johns Hopkins: the RiverStyx Foundation.

The RiverStyx Loop

As a long-time funder of Hopkins research, the RiverStyx Foundation is a somewhat unique philanthropist organization. According to their website, it takes its Greek mythology-inspired name as a call to attempt to connect “life and death, shadow and light, conscious and unconscious…[the Styx was] a source of power for the Gods, giving life and taking it away.” It funds things that “fear, ignorance, and puritan influence” have repressed and relegated, resulting in an unnatural separation into dualities, and those dualities aren’t going to just non-dual themselves.

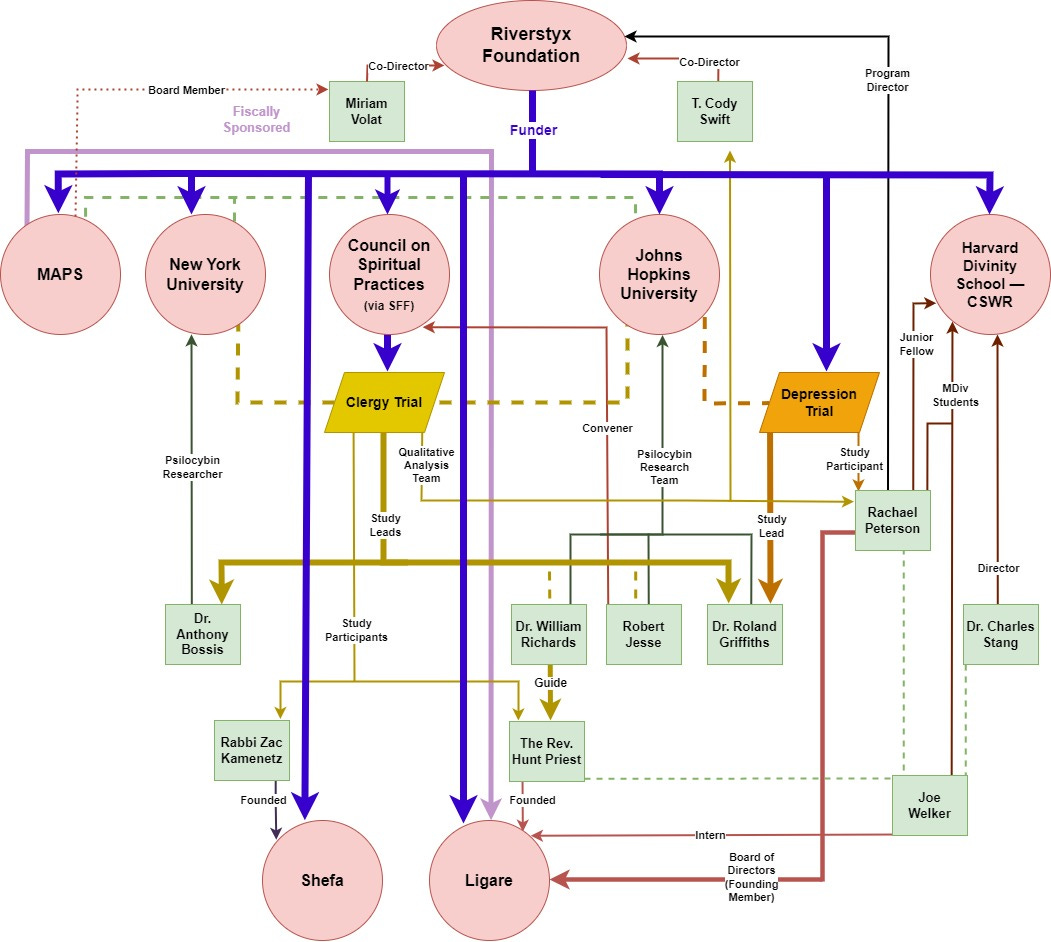

To recap from part two, in contrast to Dr. Roland Griffiths’ assertions that the study “is not about changing culture,” RiverStyx seems to see the projects they fund differently. Their funding priorities, per their website, focus on “social transformation” and “high-leverage social change” in hopes of “effectuating enduring change in both cultural awareness and social policy” for little-funded projects. In the religious professionals study, RiverStyx funded two such non-profits: Ligare and Shefa, a Jewish psychedelic non-profit created by Rabbi Zac Kamenetz.

In addition to environmentalism and drug policy reform, RiverStyx co-director T. Cody Swift has been a quietly influential player in psychedelic research at pivotal periods before many other philanthropists ever got involved. In contrast to some bawdier social media personalities, Swift has chosen a low-profile and a special interest in the spiritual side of psychedelics, most especially in Indigenous groups. He deserves credit for being a long-time donor to peyote conservation when such efforts are often extremely underfunded, and for seeming to have come around about the importance of researching risks and harms in psychedelics.

Swift has played what Dr. Roland Griffiths has called a “seminal role” in psychedelic research resulting in a close friendship between the two. As a result, RiverStyx’s donations to Hopkins have coincided with appreciable access for Swift as a direct research partner; Swift has worked with Dr. Richards as a psychedelic guide and qualitative analyst off and on since 2013. And RiverStyx has funded MAPS with over $3.8M since 2009, including $2.8M for their MDMA research, research covered in part in Cover Story.2

RiverStyx’s ethos describes a preference for more direct relationships with their grant recipients, often smaller organizations: “We develop trusted partnerships with organizations reducing the need for arduous reporting and bureaucracy.” On the one hand, this might suggest they allow grantees a degree of autonomy. But it also may be why conflicts of interest can feel extra personal. And because non-profits in a capitalist system like Ligare have to treat donors as their customers with their mission as the product, grant-bestowers like RiverStyx have the potential for tremendous influence over non-profits starved for cash.

This is especially true for a donor like RiverStyx who spreads their influence heavily around the psychedelic milieu, especially centered around Hopkins and the world of this trial. Here is a short list of grant recipients that have some connection to this trial’s social world, what Dr. Tehseen Noorani has called its “chemosocial” setting:

Johns Hopkins — $1.5M

NYU — $646k

Council for Spiritual Practices — $300k

MAPS — $3.8M

Ligare — $72k

Shefa — $67k

Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions — $45k

I think the ties here are best seen in a visual chart:

In terms of his role in what the public hears of the religious professionals study, Swift was funder, co-interviewer, analyst, and naturally, presenter of the study, giving him the power to tell the story of the data he funded, collected, and analyzed. According to one professor of bioethics I spoke with, while there can be close involvement by funders on some projects, it is unusual to be involved in data collection or management—usually, there are buffers to ensure unbiased data. It is also unclear to me if Swift disclosed his funder status when performing interviews for the study.

Swift has had a significant voice in shaping the direction of future psychedelic research, and he does seem to have real concerns for harms. Last year, Swift expressed a desire for a more responsible direction for the field, saying in August 2022, “I don’t think there’s been enough space to talk about the potential risks, psychologically or even sexually, that we’re seeing now.” But this potential shift arrives too late for many, including for abuse victims and survivors who were under the care of research bodies funded by RiverStyx. There have been times when psychedelic elite strategists appear to have a vow of not embarrassing each other while victims and their advocates get ostracized, exiled, and otherwise discarded into the void of The Silence.

For an organization that likes to challenge dualities—light and dark, conscious and unconscious—I think it’s worth considering that even if there are no conscious controls over its grant recipients, there can still be hidden, unconscious, “non-dual” controls that distort incentives and compromise voices.

Complex Agencies and Impossible Situations

No individual can be blamed or understood in isolation from their social system. And not all individuals will act the same within it,

This was a culture where multiple parties had multiple roles and enmeshed relationships that made it hard to act with clarity. People weren’t just in damned-if-do-or-don’t double-binds, the culture fostered triple-, quadruple-binds between role commitments.

Don Lattin's book God on Psychedelics opens with a discussion of the religious professionals study, where Rabbi Kamenetz expressed some uncomfortable feelings around Hopkins guide Dr. Bill Richards' influence. I have no desire to tell any of his story for him, nor do I imagine Lattin’s book tells the full story. But it does show that the relative power of suggestion (and resistance to it) is going to vary from person to person. All the same, resistance to this integration appears to have been in spite of the felt influence, not proof of its absence. Each study participant who wishes to tell their story in their own time should get the chance to define themselves as individuals—not neatly wrapped up in anybody’s “high-level finding.”

I must also say that in my experience, for whatever it’s worth, Rabbi Kamenetz has publicly displayed what I felt was sincere concern for abuse and other issues happening in psychedelics, and has occasionally made public comments in resistance to The Silence despite his at least equally-difficult situation. This is also my experience with Rachael Petersen.

(Disclosure: this next part is very difficult for me. Rachael would become a good friend, and it pains me to write about her at all, for she is more than capable of telling her own story—after all, she has before.)

I first met Rachael as part of an interview panel for the qualitative research team for a job I was very happy to apply for despite being very unqualified. After an earlier successful career in environmental activism, Rachael had been a success story as a psilocybin trial participant in a Hopkins depression study. Thanks to her talent, she was hired by RiverStyx as Psychedelics and Religion Program Director, and would also be hired by Hopkins for the clergy study’s qualitative research team. She would also be a Junior Fellow at Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions (CSWR) before later becoming a master’s student.

In early 2020, I felt lucky to be a master’s student who had managed to wiggle his way into a reading group with her, another former religious professionals study participant, and a few others associated with the Center. We would soon develop ideas around a new field of “psychedelic chaplaincy” that turned into a panel for the CSWR.

Rachael, a sharp, heartfelt, and sincere person, shared her story about how her trial experience transformed her mental health and spiritual life. However, as she would later write, reality was often more complicated. In late 2022, she wrote a powerful piece for the Harvard Divinity Bulletin about the dark side of her trial experience that she had felt some pressure to conceal, and very bravely revealed. It received widespread, deserved acclaim among psychedelic insiders and outsiders alike. It was crucially important, nailing the coffin on an old, bad, idea held preciously by psychedelic medicalization activists: the dangerous victim-blaming notion that “there’s no such thing as a bad trip.” Rachael’s piece made that position utterly untenable among insiders. Even before this, she had demonstrated some measure of independence from the Hopkins influence: in 2020 she wrote for Psymposia about concerns of researchers “brainwashing” participants into ecological attitudes, and we collaborated on a panel with another trial participant for the non-profit Chacruna Institute in December 2020 discussing the issues of mysticism in medical trials, including Hopkins. (Disclosure: I worked for Chacruna, who has received $17k from RiverStyx).

Rachael and I bonded over conversations that were not bound to psychedelics and were deeply enriching, and for me, refreshingly grounded by her critical thinking and sincere heart, including a heart for the challenges participants had faced, herself able to empathize as a former Hopkins participant, advocating for their needs.

We were each in our own impossible situation. Even in an impossible situation, I believe Rachael made significant differences in raising more attention to psychedelic harm. In addition to her bad trips piece, she was able to push for future coordination between Brown University and Hopkins on adverse events in psychedelic trials. Her piece’s influence likely contributed to the stark shifts in prioritizing risk from so-called “luminaries.”

I have to say, it’s often struck me that this tone shift from the luminaries seemed as much worried about anticipating a coming PR backlash as concern for the victims in and of themselves. They may be hurt to hear that, but it is just how it honestly feels to me. All of these influencers knew about harms that had come from psychedelics and their trials for years. So while it’s a good thing they are now talking about risks, their words are too little, too late for too many. There are lives gone who aren’t coming back who believed their overconfidence on safety. There are traumatized victims who weren’t aware of abusers that were protected, pressured to stay quiet thanks to The Silence they helped foster. And thanks to their relentless PR campaigns, there are bodies. From where I stand, the primary traumas that need to heal in the psychedelic field are moral injuries. But if psychedelics are the driving locus of your moral compass, you cannot heal the moral injuries they caused. That’s one of the problems with idols.

I have to close this difficult section with one more anecdote: in July 2022, RiverStyx sponsored a $20k gathering with the participants—not to trip, but for support. I have zero idea what was said on that retreat and wouldn't tell if I knew. But it also shows an example of how some “chemosocial worlds” should not be read flatly. While I remember feeling uncomfortable about it, emailing a journalist for the first time with the sense that something wasn’t right here, that a weird vibe was emerging, I found out that participants had requested it and told the journalist I made a mistake. I remember talking to Rachael about it, while I was in the throes of wanting to break The Silence with more conviction, but my inconsolable attitude wasn’t actually what was needed in that moment—Rachael wanted to focus on being able to show up at the retreat for participants and advocate for them, their individuality, and their dignity. To fight for the complexity she didn’t get to have when she was first a Hopkins success story, that she had to fight for herself. And despite our impossible situations, I think she was exactly right to do that. And as for everything else, I know she saved lives.

The Code and the Smile

The obvious problem with having conflicts of interest is that they compromise our judgment, sometimes in ways we can’t see. With conflicts of interest, they compromise us unconsciously in our blind spots as much as anything conscious. There’s just so much more in our blindness than any psychedelic vision. Sometimes the drugs give a blind vision to what was happening right in front of us, right in our midst, in what we participated in. And the more these multiply, you end up stuck in twenty different roles with different needs for those roles, unable to make decisions that might be needed. When The Silence is the backdrop, its Code becomes the only legible guide to navigate these conflicts.

RiverStyx’s slogan is apt: “Philanthropy at the Edge." In many cases, this philosophy has been to the benefit of those marginalized by society. But in my opinion, this philosophy also enabled a research culture that went far over the edge of professionalism. While I could assign victimhood to anyone caught in it, I do not want to rob anyone of their agency for the choices they made, because I feel all of us who got indoctrinated into the psychedelic medicalization movement had pieces of our agency taken from us as we were dosed into someone else’s agenda.

I could not abide by the Code, and so I cut ties with its adherents. Along with it, I cut off my social ties and what seemed to be the future of my dream vocation. And yet, until I found the words for this series, The Silence reigned over me in exile.

When the Code of Silence dominates, it corrupts all moral integrity of anything pretending to be spiritual. It freezes people who want to trust leaders, and it chases out those who can’t. And it twists the moral character slowly of all involved into thinking, hey, maybe this isn’t so bad. Maybe it’s not so bad that someone could be given high-suggestibility drugs and inculcated into someone’s dream.

The Silence reigns loud over our worst self-protective instincts. The Silence grows like kudzu throughout any toxic culture. The Code becomes the cultural default mode network, and no psychedelic can take it offline.

I tried to do what I could to push back on what I was seeing and feeling. With Ligare, I tried for months to make things better privately. The Rev. Priest promised he would let me talk about my issues with a wider Ligare audience, and then didn’t follow up on it. In what started as a summer 2022 talk of reconciliation, he told me I had been “impatient” about risks.

But I have to give some credit—he did include and support a piece I wrote for his newsletter talking about psychedelic risk that March, and others in Ligare expressed appreciation for me writing it. And for a lot of this time, I was struggling with my old collective Messianic complex around psychedelics turning into a collective demonic complex, which no doubt created disonnect. And in March 2023, Ligare had a webinar featuring Rachael Petersen and Dr. Charlie Stang to talk about her impactful piece. But I don’t know if he ever quite understood why I thought a Christian organization should be deeply concerned about the hidden theologies and subcultural norms it had inherited with stronger-than-normal trust.

Because I was so frustrated and angry, I asked him if he would be willing to have his bishop mediate, but he didn’t want him involved. All I ever wanted was to share a full spectrum of the complexity of unknowns around psychedelic science, especially long-term impacts, and to stand up for abuse. I told Ligare that if they continued to step up into public leadership, then I would have to speak if things didn’t change.

There’s a lot more puzzle pieces I have to leave in the box. But with everything here—not singling out any organization, but so many psychedelic subcultures—what stands out the most are the small moments.

For me, it’s The Smile. I’m not naming names, or saying we all have to be dour. I mean a very specific kind of Smile, that I think a lot of people who have been in toxic psychedelic situations (and probably lots of other cult survivors) know what I mean.

All I can say to anyone out there is if you ever find yourself looking to buy back your voice, a moment where you probe for a crack in the Code to say what can’t be said, and if you get that very certain kind of motherly, fatherly Smile behind the Silence? Take. That. Sign.

Conclusion: The Tablecloth

I was angry for so long. And I kept thinking, I can't live with myself if I don't say anything. And so I started doing more of a deep dive into researching this series, going back through my emails, going through books. And then I rediscovered something that completely changed how I saw everything.

At first, it was a puzzle piece I wasn’t sure could be part of the 399 other ones, but it’s far too out in the open not to be. It’s practically part of the tablecloth that 40% puzzle is laying on. And it is what convinced me that I had to write this series. I will talk about that in the next piece.

Note from 6/12/24: Rev. Priest says in an email, “I have never felt called to be a facilitator” and “have never done that.”