An Update on the Johns Hopkins Clergy Study

A spiritual conference in the midst of an investigation

It’s been nine months since the Religious Science of Johns Hopkins, a whistleblowing series on a psychedelic clergy study. I called for an investigation into the study, and I promised an update with any responses.

The primary update is that the religious professionals study has been under investigation at Johns Hopkins outside of the Center for Psychedelics & Consciousness Research (CPCR). According to a source with knowledge of the investigation, the CPCR also ran its own internal review. The CPCR did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

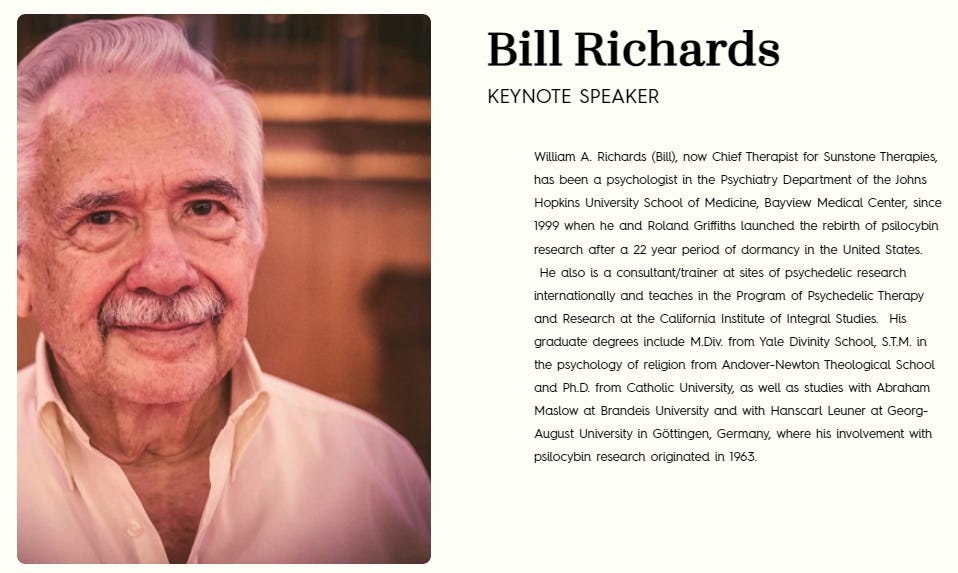

Part of this investigation was looking into an alleged potential boundary violation by Hopkins researcher Dr. Bill Richards as described by Episcopal priest and study participant Rev. Hunt Priest. Rev. Priest described Richards laying hands on his head akin to an “ordination,” prompting a “Holy Spirit” experience as an origin story for starting his non-profit Ligare: A Christian Psychedelic Society, which I interned for from September 2021 to April 2022.

Despite an ongoing investigation into the study, Dr. Richards is keynoting a conference hosted by Rev. Priest’s non-profit Ligare, as well as giving a $35-a-ticket talk (discussed further below).

The circumstances raise questions that, so far, neither has addressed publicly. In a reply to a request for comment for publication, Ligare declined to offer a comment about Dr. Richards on the record at this time. Dr. Richards is also offering a workshop at the prominent Horizons psychedelics conference on May 8th. Horizons did not respond to a request for comment.

There have been several other updates related to the clergy study in the past nine months; in October, the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Roland Griffiths, passed away from cancer. In March, the New York Times ran an extended piece about related issues with Dr. Griffiths’ lab at Hopkins.

Before getting to the updates pertaining to this story, here’s a recap. To dive in further on the specifics, click on each header or read it from the beginning.

Recapping the Issues

Researchers and donors to the Hopkins/NYU study have been in the public record about the motivations of their research, some of which appear to be a social goal of advancing their religious and spiritual beliefs about psychedelic drugs and mysticism through the reputation of science.

Ethical issues around psychedelic suggestibility:

Psychedelics render people highly vulnerable to the influence of those who administer them, causing significant ethical issues. Hopkins’ guidelines called for the bond between researchers and participants to be made even closer than usual for safety purposes. However, this seems to leave participants more vulnerable to undue influence both within and beyond the trials.

Some of the ethical implications of psychedelic suggestibility include the possibility of belief changes to those of guides, identity shifts with sense of self, and an “afterglow” period where one remains open to influence after the acute effects are gone. When psychedelic researchers have not paid careful attention to the effects of suggestibility in their trials, it has created what some researchers have called “chemosocial matrices” of social groups between participants and researchers. While this has potential benefits, it can possibly lead to both poor ethical outcomes and issues with the quality of research.

Covered more in the March New York Times piece, Dr. Matthew Johnson said in 2021, “Even short of sexual impropriety, psychedelics might magnify the subtle abuses of differential power that can be at play in the routine practice of clinical psychology or medicine. It can be challenging to be associated with what might be one of the meaningful experiences in a person’s life. The scientist or clinician might, perhaps without explicit awareness, fall into the trap of playing guru or priest, imparting personal philosophies without a solid empirical basis.”

A large donor to the study acted as both an interviewer and a data analyst

A major donor of the Hopkins study, T. Cody Swift of the Riverstyx Foundation, acted as both an interviewer and analyst during the study. Another employee of Riverstyx was also a data analyst for the study.

This degree of donor involvement gives significant power to a donor to ask questions to elicit certain kinds of responses, then the power to interpret the responses.

The same donor also funded participants to start psychedelic religious non-profits

Swift’s Riverstyx funded two participants to start their own non-profits. One of these non-profits, Ligare: A Christian Psychedelic Society, was founded by Rev. Hunt Priest, a priest in the Episcopal Church, in April 2021.

The relationships between participants and researchers were extensive and highly unusual

There are more interrelated relationships here than could be covered. One manifestation of these unusual entanglements was a July 2022 retreat with participants and researchers, which the New York Times piece covered.

For another example of the close ties between some researchers and some participants, the Rev. Priest attended a peyote ceremony with another study team member arranged by Riverstyx.

According to an Esquire article released after this series in October 2023, before Priest’s treatment, “Dr. Richards said with a smile, ‘You’re about to meet God.’”

The Rev. Priest wrote the following of his trial experience: “After asking permission, Bill placed his hands on the top of my head as I sometimes do when offering healing prayers and anointing a parishioner (the sacrament of Unction) and Darrick sat at my feet and allowed me to press my legs against him as I had done for my wife when she was in labor with our son.”

While potentially still under the influence of suggestibility in the “afterglow” effect, Rev. Priest described: “In our conversation afterwards I asked them what all that energy was about. Bill smiled and said, ‘In Christian language, I think we call that the Holy Spirit.’”

Later, the Rev. Priest described this experience as evoking ordination, with “a desire to make the experience available to all who need and desire it.”

In a October 2023 piece for Esquire released after this series, “Someone laid their hands lightly on Priest’s head, and the electric current increased its voltage tenfold, hundredfold, thousandfold, and that current shot right out the top of Priest’s head and he began speaking in tongues…After he returned to himself, Priest knew he must return to Georgia and do something more daring than just lead a church. He had to change the whole of Protestantism. Which is what he’s carrying out now.”

Dr. Richards, who in 2015 wrote a book detailing his psychedelic theology and desire to integrate it into Western religion, said at a 2022 Ligare talk he was “[happy that] Hunt is devoting his life right now to facilitating this emergence in which we so desperately need.”

While Rev. Priest’s trial description was received by a study team member’s inbox as early as January 2021, it is unclear if it was in his original trial description. In April 2021, Rev. Priest founded Ligare with financial support and board membership from Riverstyx.

It is unclear if any investigative actions were taken by Hopkins around Rev. Priest’s disclosure until after this series was published.

It is unclear which investigators knew of the incident that Rev. Priest had publicly shared on podcasts and in writing multiple times.

There are now questions about whether the experience happened as Rev. Priest has repeatedly publicly described, but Rev. Priest has not clarified this publicly.

Despite this and many other concerns around the Rev. Priest’s behavior, Riverstyx continued funding Ligare in February 2023.

In addition to concerns over Ligare’s communications, direction, and the safety of Ligare’s activity, with no information about risks on their website’s “Resources” page (archived May 2023) until after this series, I terminated my internship with Ligare due to disturbing conversations with several members of Ligare’s leadership team downplaying concerns of abuse in psychedelic clinical trials.

The presentation’s message tracked with what appears to be the goals for religious change for the study and with what psychedelic researcher Rick Strassman, PhD, predicted in 2018:

“One should retain a healthy skepticism for the ‘religious leaders’ studies now occurring at New York University and Hopkins…It is inevitable that researchers will use these data to support their notion of a ‘universal, core, primary mystical experience’ underlying all particular faiths.”

The New York Times Story

In examining issues in the research environment fostered by the late Dr. Griffiths, Brendan Borrell deserves credit for tackling a contentious story that would be hard to leave anybody fully satisfied. After conducting a wide range of interviews, Borrell released perhaps the most critical piece on psychedelic research in a mainstream media outlet to date, which is to say it is one of the only mainstream media pieces in the past decade to include a significant amount of critical examination (a recent Washington Post article is another example).

This newsletter received an attribution link with many of the themes here independently confirmed, though not all; the Times story focused more on the tensions between Griffiths and Johnson, who had been a colleague of Griffiths for nearly two decades. The piece noted Dr. Johnson’s criticisms that “Dr. Griffiths has run his psychedelic studies more like a ‘new-age’ retreat center” and like a “‘spiritual leader’… infusing the research with religious symbolism and steering volunteers toward the outcome he wanted.”

Some commenters framed issues at the Center as a Johnson versus Griffiths battle of jealousy despite the breadth of issues that have been raised at the CPCR. This also ignored the wide-ranging interviews conducted from those on and off the record, and that the description of this environment was far from being held only by Dr. Johnson. Other industry reactions defended Dr. Griffiths as less of a leader than a follower, a victim of psychedelic forces rather than a driver of the problems.

The Times piece can be further informed by watching the dinner given in Dr. Griffiths’ honor at the large MAPS conference last June, which included a now-infamous painting commissioned by Riverstyx’s Swift, with one Hopkins researcher describing Dr. Griffiths as, “A new kind of archetype; he’s a sage for our age.”

Dr. Griffiths also telegraphed his desires for psychedelic social change and intentions for the religious professionals study three years ago during an interview with Jordan Peterson, recorded March 2nd, 2021, starting around the 2:11:00 mark.

Griffiths: “I’ve concluded, and it sounds to some like an overstatement but I don’t think it is, that actually unpacking this whole situation is crucial to the survival of our species…if we can understand the kinds of experiences that give rise to mutual caretaking, then we have the ability to solve all kinds of horrors that our cultures have imposed on us, and you could imagine interfaith dialogues that could come out of exploration of these kinds of experiences across faith traditions, and my guess will be the discovery is gonna be, ‘Well wait a second, the bedrock core—and this is the perennial philosophy—the bedrock core of most of these traditions is really quite similar.’ So whether the future is integrating into existing religious institutions, or seeing an evolution of our cultural institutions that can incorporate this sort of thing is, you know, I think a question.”

Dr. Griffiths then cautions about the risk of integrating psychedelics into society too quickly, giving an argument against psychedelic legalization in favor of a careful integration with religion, part of a theory of social change to resist cultural backlash:

Griffiths: “Look what happened when the Spanish came over to Mexico, they actively stamped out the use of of psychedelics. I think at the core if we’re not careful, it can be destablizing to culture, and then culture’s gonna come back and demonize them, which is exactly what happened in the ‘60s. So I am concerned about the excited movement towards decriminalization and legalization.”

Peterson follows with some extended thoughts on Carl Jung and the need for healthy tension between religious dogma and religious experiences, with Griffiths discussing psychedelic risks. In addition to the safety concerns of this, Griffiths brings it back to concern of cultural backlash:

Griffiths: “If I can come back [to thinking] culturally, and how we integrate this, I’m almost thinking of this now in an evolutionary sense, we have to evolve the cultural institutions that can create the containers around these experiences such that they don’t threaten our existing institutions which will become reactive and demonize them and shut them down, and figure out the intelligent use of these compounds.”

Peterson then turns to the religious leaders study, hinting at the reconvening of participants that would take place in July 2022:

Peterson: “Now you’re inviting religious leaders to participate in that process. So just out of curiosity for example, you’ll have this assembly of religious leaders who have undergone this experience. So will they commune? Wil they discuss collectively the implications of this? Because you know, it’s necessary to start thinking about how those social structures might be evolved. You have this first batch of people who have already made an ethical commitment and a disciplined choice, it would be fascinating, it seems, to put them together for three or four days and say, ‘Look, what do we do with this?’ You’re in a unique position to see what answers might arise from that.”

After discussing Harvard Divinity School’s psychedelic chaplaincy program, which I was involved in early discussions with, Dr. Griffiths concludes this section by pointing to his desire for a way for psychedelics to not only be given to people in need of healing, but “well persons,” an idea popularized by Hopkins’ spiritual mission of their research since Michael Pollan’s first New Yorker article on psychedelics in 2015.

Griffiths concludes this portion of the Peterson interview:

Griffiths: “Right now we have no path forward in our culture for approval for administration of psychedelics to well persons….this is part of the co-evolution that needs to happen.”

A month after this interview, Rev. Priest’s Ligare was started with seed money by study donor and researcher T. Cody Swift of Riverstyx, with a Riverstyx and study team member on the board. In January 2021, and throughout 2021, Rev. Priest repeatedly described his origin story in the study, which entailed describing an alleged boundary violation.1

A Conference in the Midst of An Investigation

In spite of an ongoing investigation looking at Rev. Priest’s description of his trial experience with Dr. Richards, Rev. Priest announced through his newsletter on April 8 that his “personal mission” of combining psychedelics with spiritual direction had come to pass:

The conference has since sold out, but tickets for an accompanying $35/a head in-person talk from Dr. Richards are also available as of publication.

In response to an email request, Ligare did not offer a comment for publication on Dr. Richards’ participation or the ongoing investigation. Ligare clarified in an email that in response to community feedback, the previously planned “Certificate of Completion in Psychedelics and Religion” would no longer be offered due to the potential for being misunderstood as a training certificate rather than a certificate of attendance.

More information on the conference can be found at the URL www.ligare.org/store.

Responses

Before and throughout the series I made several explicit invitations to those involved to send any comments they would like published and for corrections. By and large, I did not receive any responses from those involved, and none who wanted to include a public comment. I received one fact-check, which was resolved with that person immediately after publication, who did not want further comment.

Response from Hopkins

As mentioned in the intro, Hopkins’ CPCR has not publicly responded. I reached out through the Center’s website to comment before this piece about the status of Dr. Richards, given his public engagements, but did not receive a reply.

Response from Ligare

In nine months, Ligare has not yet publicly acknowledged the series. Last week, in the first correspondence since the series, Ligare shared they believed there were factual errors and misrepresentations but have not yet given specific corrections to be published.

Before the series was published, there was no information about risks on their resources webpage, as seen in an archived snapshot from May 2023, despite existing for two years as an advocacy and educational project aimed at Christian populations. They have since publicly begun signaling some discussion about risks; in an April newsletter, Ligare stated that “our ministry is focused on education, connection, and harm reduction.” This is a marked difference from my time in Ligare, in which I terminated my internship early in part because of their recklessness.

Since this series was published, they have drastically updated their website to include issues raised by this publication. To be clear, while their website has made improvements to overall information and messaging, I would not endorse the information on it for Christian laypeople. Then again, my position on psychedelics has changed considerably, in no small part because of my interactions here.

While Ligare uses “safe” and “legal” as a mantra for what they promote, this belies that many Ligare affiliates and leaders use psychedelics in illegal settings. In the progressive Christian book Discovering Fire, in which Rev. Priest has a foreword, the author says that he attended one Ligare-sponsored retreat in Colorado in 2022.2 This would be, at minimum, federally illegal. As an intern, I once personally helped connect someone who contacted Ligare with a practitioner who was practicing illegally.

Lingering Questions

There is no known timetable for resolution on the Hopkins investigation, and I expect Hopkins leadership to feel their hands are tied from saying something publicly as it’s ongoing. In the meantime, Dr. Richards is still listed as a research psychologist on the Hopkins website as of publication. Have his actions have been cleared in this investigation? If not, why is he doing the retreat with Ligare? If he is cleared, how and why? What actually happened? And as for Ligare, why host him for a paid event without ever addressing this?

Update: three weeks after this piece, I was copied on a cease & desist letter sent to Substack in an attempt to censor my whistleblowing. Here is the letter with my response.

Note: one sentence has been corrected for clarity (see footnote 1).

This sentence has been corrected for clarity. It originally read: “In January 2021, and throughout 2021, Rev. Priest repeatedly publicly described his origin story in the study, which entailed describing an alleged boundary violation.” Rev. Priest privately described his origin story in an email to a study team member in January 2021 and then publicly in late 2021.

Wolsey, Roger. Discovering Fire: Spiritual Practices That Transform Lives (p. 328). Quoir. Kindle Edition.