Meet the Soul Engineers

Psychedelic billionaires and the project to patch our religious "mind virus"

An Airbag Saved My Life

When we still had malls, I remember buying my first Radiohead album, OK Computer, from FYE Music in the early 2000s. For anyone who did the same, the opening chords of “Airbag” ripped into our understanding of the world, a jarring musical thesis staring at the intersection of technology and capitalism, the critically acclaimed soundtrack of dot-com horrors we knew yet not. With songs like “Electioneering” and “Fitter Happier,” Radiohead’s issue was not that anyone was making money. It was about what it was doing to our souls and the nameless who were doing it to us. When I went back to buy the OK Computer tour concert DVD, Meeting People Is Easy, the box art made the subtext clear: “You are a target market.”

This came back to mind when I read a report released a few weeks ago by the psychedelic drug industry watchdog and third-railers Psymposia. The report describes how the Psychedelic Science Funders Collaborative (PSFC), a group of psychedelic enthusiast millionaires and billionaires, has been socially engineering a movement to capture regulators, social media narratives, and, as I first spoke out two years ago, even religion. The PSFC comprises around 200 members, with a core contingent in Elon Musk’s orbit. While their project is presented on one level as a goal to promote new medical treatments, what has been clear is that another goal is to evangelize a non-medical spiritual mission.

For those who have followed my Substack, this was previously shown in the clergy study I blew the whistle on, aspects of which I am still trying to understand. What this new report reveals is how that study was what we all hope to be: connected to something greater than itself.

Psymposia are a group who are no stranger to controversy. While I don’t share their political or theological background, and while those reported on will dispute some interpretations of the facts, the report appears to be seriously vetted by a third-party and published in the face of potential legal retaliation. Since some of my stuff was mentioned, I am going to focus on the facts and how they relate to my concerns.

Also, while this isn’t the focus of what I’m going to talk about, I want to acknowledge the role of the report’s contributing author Meaghan Buisson in continuing to warn others how the therapies promoted by the psychedelic industry led to her abuse, discussed at length in a podcast four years ago this month. Others have tried as well, to largely deaf ears in the industry, in part because these therapeutic practices appear as an extension of the industry’s amorphous psychedelic theology and would implicate its most prized studies and practitioners. While I won’t speak to all that directly, it’s certainly relevant to what’s going on here.

I also need to say that I don’t believe that the psychedelic elite nor the wealthy (at least most of them) are on a personal level any more evil than the average person (at least most of them). A decade ago, I worked for several years on the IT help desk of a hedge fund. In the office, the ultra-wealthy were pretty normal, because people are people. I’m grateful some Reagan-era Republicans unwittingly funded my ayahuasca retreats in the California desert. Those experiences played some role in my return to Christianity.

I once was enmeshed in the psychedelic spiritual-industrial complex and am still unlearning its logics. I have left it to become a small town pastor, though I still go to Phish shows sober (there are dozens of us). Still, I recognize that for many, any Christian expressing concern about this might sound alarmist, demonizing, and hypocritical. And, well, we do get hysterical sometimes. We do demonize when we shouldn’t. The Church practically invented spiritually-charged abuse for the sake of a utopian mission. Unfortunately, even for those who find us as broken clocks, our concerns are sometimes legitimate.

So I believe the public needs to know that there is a well-funded and well-connected group engaging in what the report calls “cultural engineering,” priming the public to embrace not just a class of drugs, but a set of worldviews about them which are intertwined with their mission. This should give pause to anyone who might consider both intended and unintended consequences that may come from technocratic manipulation of the human spirit.

What is also evident is a historical trend. The psychedelic movement has been a long line of scapegoating to purge narrative threats. Abuse victims, critics, whistleblowers, and other dissenters are the latest, but the dynamics of scapegoating go back farther. Sometimes, the scapegoat of the movement’s failures were in singular figures like Timothy Leary (who did plenty to deserve condemnation) or Richard Nixon (same). But often, the psychedelic scapegoats have been bigger and impersonal: the DEA in their evil drug war, or religion in its dogma, or the psychiatric industry and their SSRIs, or the FDA and their ignorance, all convenient enemies to blame for the failure of psychedelic drugs and the people who love them at the expense of a wider consideration for what role all these groups play in a functional society. I sometimes wonder if scapegoats fracture critical elements of the movement itself, as factions within psychedelicism each have competing ones. My advocacy to try and protect the vulnerable has carried the narrative risk of scapegoating priests, researchers, and journalists who were, nevertheless, engaged in unethical behavior.

In all this, the scapegoating often turns internal, with the ego demonized and expelled more than once, only to sneak back in as it does. More horrifically, the survivors of pseudoscientific psychedelic therapy abuse have had their psychological defenses scapegoated to allow for predation, both by abusers and their enablers.

While the specific scapegoats are unique in this history, this is just part of the story of humanity. To say the psychedelic movement is uniquely evil would be to then scapegoat the movement. But to ignore how it participates in ritualistic scapegoating would be folly, and plenty of that is on display in Psymposia’s report, such as in coordinated smear campaigns in a rush by funders to save a doomed MDMA application to the FDA. And while all of us can be enticed by temptations to scapegoating, there should be no false equivalency where there is asymmetrical power.

So I neither want to engage in scapegoating myself, ignore the exhaustively reported actions, nor recapitulate them all, but speak especially to what I see spiritually going on for those who want to get a handle on this. I am still trying to make sense of the dangers here alongside the many stories of positive psychedelic experiences. I have my own stories, or I wouldn’t be writing this.

But if psychedelics are said by psychonauts to be “non-specific amplifiers” of our psyche—and arguably, money is as well—then the combined power of psychedelics and money amplifies the sins of the powerful, projected onto society, leaving the rest of us to care for what, and who, is broken in the aftermath of their vision.

Funding disclosure: I have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. My ministry is partly funded by a few people who read my sermons online, but primarily by an undisclosed group of mostly retired Vermonters.

In Philanthropic Fairness

As I’ve chewed on the report, I’ve tried to imagine the perspective of the wealthy here, as if I were back in their third home helping them set up WiFi in their Montecito breakfast room all over again. Some of their bios are profiled here. They are not a monolith, but have diverse interests unified by a common goal in expanding psychedelic drug access. Some are driven by being close to personal tragedies like heroin overdoses that many of us can feel who have ever been close to addiction. From many of their perspectives, I imagine they see their project as just pragmatic in trying to solve the intractable problems of depression and PTSD, while also feeling they have a wonderful spiritual secret the world needs to experience.

Also, the PSFC organization describes itself as a “community” facilitator, a place where members are mostly not giving directly to the PSFC organization. Rather, the PSFC gives advice on where to give, but members don’t have to listen to what they suggest. While this might be benign, it also perhaps downplays the power of PSFC leaders in shaping the direction of channeled funds.

In a webinar, PSFC’s leadership don’t seem to fit the report’s description of “syndicate.” In many ways, they come off as a sweet group of well-intended thoughtful people who I could imagine in my church. This is what makes it hard to square the persons with the actions, which I can best make sense of through looking for greater mechanisms. If there is no malice, there is perhaps overwhelming mimetic desire: the desire to emulate healing they’ve had, to grow the movement they’ve been enlivened by, and replicate an inspiring vision. But desire can become more binding into moral compromise than we realize.

Some insiders have defended the PSFC by saying funding groups like this are just how the world works. Is there truth to that? Take, for example, my local community land trust. They pool resources for a shared mission, host events to promote ideas about affordable housing, and engage local leaders in conversation to help craft bills. That’s not sinister.

But if I learned that the land trust was directing the majority of its funding to a PR campaign that included “training journalists” to massage coverage, using proxy groups on my town’s online forum, and if this housing nonprofit were doing all that because they wanted to build communes for their new religious movement, it would look like something out of Wild Wild Country.

Still, I imagine some members of the PSFC don’t even care about the spiritual side of things, just medical treatments. Some of these funders are paying for important harm-reduction and safety research that a corporation might not, stepping in to fill in research gaps for “market failures” when a lack of patent protections made psychedelic research unprofitable.

And if they do care about spiritual transformation, maybe it’s understandable that they see themselves as visionaries, doing the hard work of building things that will help people spiritually “wake up.” To return to the mall for a second, many in the PSFC are Gen Xers who might have even once been inspired by OK Computer in college. Is it possible they actually have the antidote to tech alienation? After all, we’re not just alienated from each other these days, but truth itself, and the implied sola experientia tenet of the psychedelic New Reformation says that personal experience is the only thing you can trust: “I don’t know much, but I know what I felt on that trip: connection, rebirth, insight into my trauma and ignorance. I can count on that.”

In their own minds, there’s no syndicate gatekeeping a cottage industry that’s a hybrid between pseudoscientific therapy and a new religious movement. PSFC’s leadership sees themselves as managing an “overwhelming” amount of psychedelic interests, not trying to culturally engineer, but bringing tech, finance, and D.C. savvy to optimize and scale the gift. Some have suggested it’s just an email list of friends trying to do good who could buy a yacht instead.

Yet despite it all, I cannot look past the amount of energy that says it goes towards love that winds up in a narrative war. I have also wondered: is an even deeper spiritual manipulation inevitable when New Age attitudes get amplified with money and drugs? The parkour trainer Rafe Kelley, who has said he had positive MDMA experiences, had this to say in a recent podcast with Paul Anleitner on growing up in that environment:

“C.S. Lewis talks about this in The Abolition of Man. Traditional philosophy asks us, ‘How do I live in accordance with nature, in accordance with the Dao?’ whereas the technological worldview asks, ‘How do I bend nature to my own will?’ …I grew up in the counterculture, the hippie movement, New Age spirituality, and there’s a sense that this was a return to the land. This is a reclaiming of our relationship to Mother Nature. And yet at the same time, I think it had this egoistic drive to overcome that was not fully metabolized. And I think that they saw Eastern spirituality as a set of technologies that can free the self from constraint. And that ultimately led to an enormous amount of narcissism and very dysfunctional patterns of behavior with people.”

Despite its efforts, the technological approach to the soul cannot fix what is emergent from it.

But if you want to beat Big Pharma, maybe you have to become Big Pharma.

Opioids and The New Familiar

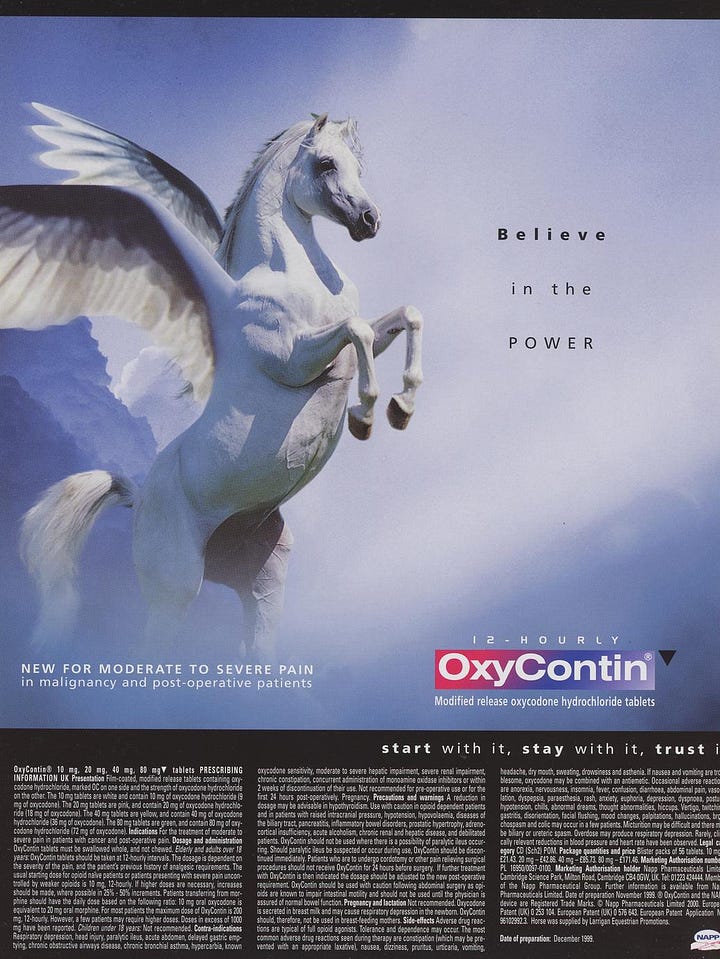

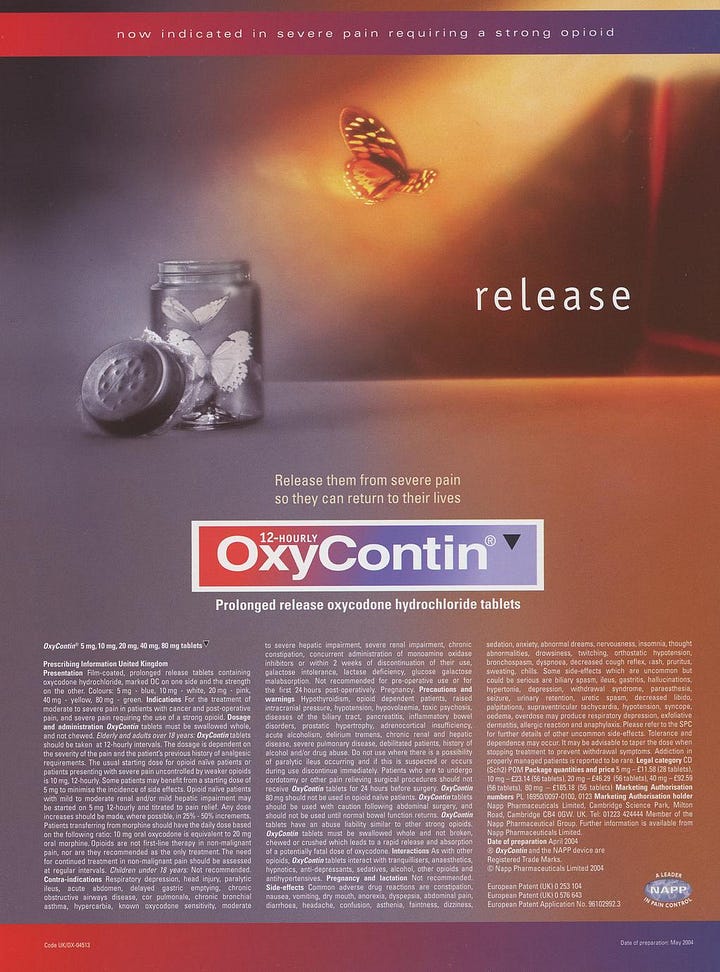

As the report shows, it was not long ago that miracle drugs were pushed on the American public by a coordinated well-funded campaign. Unlike opioids, you are not being targeted for financial profit this time, but a greater vision that needs your political cooperation.

According to the report, rather than funding science, the majority of the PSFC’s $125M three-year funding priorities was dedicated to PR. With many parallels to what led to the opioid crisis, the report describes a plan centered on narrative manipulation, exploiting veterans for public sympathy, and attempting regulatory capture of the FDA. Note that while the FDA ultimately rejected the MAPS application for MDMA therapy in August 2024, the report details ongoing attempts to embed within the Trump administration.

It seems a driving impulse has long been changing the public perception of psychedelics, taking science-by-press-release to the Nth degree, exploiting empathy to overstate benefits and downplay risks. While that is the front-end development of cultural re-programming, the back end includes ethics washing, drug safety theater, and “training” funded activist journalism.

But to complicate the comparison to the opioid crisis, there is not only interest in replicating a Big Pharma model that goes through the FDA, but using state-regulated quasi-therapy programs (such as in Oregon and Colorado). These state programs have been laden with issues from the start, but the point is not a belief in a single model, but simply growing psychedelic drug access and use through the PSFC’s “thousand flowers.” Meanwhile, a single large flower from the comparatively “boring” psychedelic capitalists who do not appear to share the same FDA scapegoats, Compass Pathways, just announced it is planning for possible approval a year ahead of schedule. It seems they will get to reap the benefits of the PSFC’s persuasion campaign without carrying the risk.

I have previously attributed the propaganda mechanics pushing psychedelic acceptance mostly to the common folly of our shared humanity, the social dynamics of drugs with a passionate fanbase. I think that’s still in play. But what is clear in this report is that there is also substantial centralization that gives the illusion of something organic. And this really can distort the whole information matrix that affects how the average person makes sense of these drugs. Well-intentioned journalists, policymakers, and members of the public see enough headlines and carefully curated talking points across multiple outlets and imagine themselves to be informed, when really they have been receiving the same droplets of propaganda from the same handful of faucets coming out in different pipes. Those pushing it would use different adjectives; “PR and marketing” are, after all, PR and marketing terms for public manipulation.

There is a cognitive dissonance for many in the psychedelic movement. One of the value propositions the industry makes is that these drugs are supposed to be liberatory, unlike the enslaving opioids that were pushed by Big Pharma (who, as we see in the ads above, also styled their drugs as liberatory from pain). But for many, using psychedelics to cure themselves from opioids has brought new problems. When people use psychedelics to treat opioid addiction (and I know self-reported success stories), this has sometimes delivered life-changing results. But it’s also sometimes delivered, well, other life-changing results.

We don’t really know the exact numbers, but psychedelic usage clearly leads some percentage of people to long-term psychological harm, character twists, personality changes that are not always for the better, and messianic complexes reminiscent of the gnostics swirling around the Early Church. This is not even getting to the memory-holed horror stories of when things turn catastrophically and violently wrong.

While opioids plague bodies, creating physical dependencies and overdoses, and some have found psychedelics to liberate them of that, the danger of this psychedelic project is the potential for catastrophic impact on some indeterminate number of souls, attacking mental stability, personal identity, and spiritual autonomy.

The public’s support of veterans is crucial to this, and as someone who was a chaplain intern at a VA hospital, my faith deepened by their faith, I am personally concerned about their receiving better treatment, but I’m also concerned about their exploitation. Like in the buildup that created America’s opioid fallout, the dynamics here are not always good for veteran advocates either.

For years, Jon Lubecky was the singularly most connected pro-psychedelic veteran lobbyist who has now disavowed some of the PSFC-connected groups he used to lobby for. While Lubecky has said he greatly benefited from MDMA’s impact on his PTSD, he has now struck a public note of warning, including that adverse events have not been properly recorded. He is particularly adamant against the psychedelic industry and its ulterior motives. As he said in an interview, “When medicine becomes a movement, the people who suffer are the patients, because the patients are inherently exploited for the movement.” In sharing my article on Michael Pollan’s unethical journalism that has protected PSFC-connected projects, Lubecky wrote, “Far too much ‘research’ on human subjects in this field is for propaganda value and to create activists for their political causes.”

Now it’s true that the addiction profiles and highs of psychedelics are not the same as opioids in type or scale, and it’s true that psychedelics do not usually make one physically dependent. But besides the Russian roulette chances of developing mental issues, do psychedelics also risk spiritual dependencies among those who enjoy them? I have argued yes. The risks are not just the ~10% who self-report some kind of extended harm, but, as many like Ashley Lande and William Craddock have reflected, the bizarre darkness and moral confusion that can come from someone who believes it is going well.

Some believe you are opening yourself up to the demonic, entities who pose as angels of light (or just a DMT machine elf). But even if there are no demons in your worldview, what makes combining psychedelics with a new class of enlightened therapists uniquely insidious is what I and others have repeatedly stressed: these are drugs that can render you highly susceptible, more than you realize, to the attitudes, whims, and desires of those who administer them. As the report says, “Psychedelics have been normalized for medicalized use without a real understanding of their risks, especially their capacity to render people vulnerable to influence and persuasion.” You are not just taking a psychedelic when you take a psychedelic. You are opening yourself up to the worldviews and motivations of those who cultivate your experience.

This should be concerning even if mushrooms are core for how you connect to the sacred, because being high on your own noble motives is exactly when catastrophes happen (see the Church). The greed driving the opioid crisis led to something awful. Now imagine that opioids were pushed by a group of insiders who worship the divine on sacred Oxy retreats.

Unlike the Sacklers’ more straight-forward greed, the report describes how the PSFC essentially acts as a PR and lobbying firm for something that includes a spiritual movement. One goal is to prevent unsettling stories from becoming what PSFC documents call “negative media cascades,” which, to translate, could mean “prevent the public from being disturbed,” with a desired $46.4 million in funding just for “communications and public health education.”

Part of that strategy is paying journalists one UC Berkeley-sponsored grant at a time. UC Berkeley’s psychedelic center was founded by author Michael Pollan. PSFC leaders embraced Pollan’s avowed strategy of “training” journalists as part of a “bulwark against backlash” in the public and the media. While framed as “public education,” there is reason to question this frame. As I covered earlier this year on Pollan’s journalistic malpractice in The New Yorker, it is noteworthy that a celebrity journalist professor who teaches at UC Berkeley and Harvard believes in “inoculating the public” to scandals, using journalism to vaccinate the public from being too concerned about psychedelic harms.

Another means of narrative regulation is through the UC Berkeley center’s popular newsletter called The Microdose, which claims independent journalism. But it is unclear what independence means when the Berkey center’s funding has come from those whose projects they sometimes cover; in a request in April asking if they had a policy on covering those affiliated with the center, they did not respond.

As far as the grants go—building what Pollan calls a “cadre” of reporters—this doesn’t necessarily mean quid-pro-quo, nor does it have to. Biased “training,” social network pressures, and the smallest financial incentives in a field where it’s hard to make a living are enough to selectively cover, twist, and frame bad stories to shape the public imagination to its proper end.

There are no cartoon villains here, and neither is Pollan. I do not see malice as we think of malice, but perhaps reflexive seduction: seduction into a self-therapeutic worldview that sees spiritual wholeness as something to be gained through techniques, whether practices or chemistry, which begets seduction into drugs that promise to heal the soul, which turns into seduction of others to share the spiritual wealth, even if it means some aren’t so lucky. This is just a notable, visible expression of what would necessarily emerge from this system: a movement’s self-mythology translated into something the outside everyday person can consume, then later, a mechanism for regulating that self-mythology’s ongoing narrative among adherents. Rather than consciously malicious manipulation, I believe it is more likely done through unconscious in-group imitation, the currency of belonging.

However we try to explain it, like opioids and now cannabis, this sets up a media environment where journalists fail to rigorously report about the harms of drug-based issues until it’s too late.

Pilot Program

Regular readers of this newsletter are familiar with how a Johns Hopkins and NYU clergy study produced psychedelic evangelists. In some ways, the study was a pilot program test-driving a PSFC vehicle, like an art car on the Burning Man playa to show everyone what’s possible.

Regulators found such egregious improper donor involvement that, in the words of Johns Hopkins Medicine’s Institutional Review Board, the study “significantly compromised the rights and welfare of the participants” and “significantly compromised the integrity of the Organization’s human research protection program.” As I covered, there were abundant overlapping psychedelic evangelist goals expressed by many of the researchers and funders affiliated with the study. Giving people drugs that make you open to suggestion, persuasion, and undue influence by funders acting as researchers, directly interacting with subjects without disclosure, nakedly motivated by a spiritual mission, is an abuse of both scientific principles and human subject research.

Besides the report, there was another public revelation this month. In a recent podcast, former Hopkins faculty and study team member Dr. Matthew Johnson shared that my whistleblowing led to a series of investigations, which apparently began with the study’s lead legendary researcher Roland Griffiths conducting an “internal audit” to try and get ahead of Hopkins regulators. But according to Johnson, Griffiths’ internal investigation looked like a “sham”; despite being a faculty member on the study, Johnson was never interviewed (and for what it’s worth, I never received as much as an email confirmation from the Hopkins psychedelic center that they were aware of my concerns). Johnson, who had previously raised ethical concerns, described the response as “circling the wagons... it wasn’t about ‘Okay, what was done right? What was done wrong?’... It [was] more about protection.”

Chapter 12 of the Psymposia report covers a lot of ground previously covered in my newsletter, but further shows how the whole Hopkins psychedelic research center was also essentially created as a PSFC product. The clergy study team wasn’t just loosely connected to the PSFC. As the clergy study paper acknowledges, one of the founding members of the PSFC, Bob Jesse, also funded the study through his nonprofit, helping conceive and design the study and then co-author it. He has been attempting to engineer psychedelic spirituality for over thirty years.

Besides the abundance of statements from Jesse about Hopkins’ psychedelic studies and the “reconstruction of religion,” or wanting to use science for “waking up” people to “fire on all cylinders,” or any number of public talks Jesse used to give to psychedelic researchers about their spiritual mission, the report shared another interesting quote I had overlooked. It was from 2009, a decade into Jesse’s involvement in Hopkins’ research. If this doesn’t sound like a scientist talking about science that is interested in truth, it’s not:

“Why is it important for you to know that I’m an engineer? Well, scientists and scholars are interested in truth, so at the end of the day…they go to sleep being satisfied that they’ve discovered something that they’re convinced is true. Engineers, by contrast, like to build things…. [They] feel satisfied because something exists in the world that didn’t exist before…. At the end of the day, just know that there are people in the room who are more concerned with ‘ultimate truth’ than I am.”

This checks out. Because if they were scientists interested in discovering the truth of the effects of psychedelic therapy on religious populations, why wouldn’t they run a study on all kinds of religious people, especially laypeople? Why would they target a handful of outlier clergy if not to, as Griffiths himself described, “evolve” religious institutions? With funding from researchers, several did go on to pivot their careers to psychedelic nonprofits, which is how I got tangled up in this.

The picture that has long emerged looks like the clergy were not part of a truth-seeking enterprise, but one for reprogramming religion. Some of the clergy are offended by that, and I get that, especially because most of them described positive experiences. I might have felt offended too if I were in it, but no matter the case, they all had a right to know about the unethical behavior, and so does the public.

In 2023, Pollan revealed that Jesse made editorial suggestions to every issue of The Microdose so that they don’t “exaggerate” or “misrepresent,” but Jesse was not listed on their website as a contributor. When I asked in April 2025 whether he still had this role, I received no response. Pollan’s New Yorker piece conspicuously did not mention him at all.

I have long written about the danger of psychedelics simulating profundity, manufacturing meaning without a true referent behind it, then assigning the felt-meaning to the images and phrases that emerge from the subconscious on a trip that become “insights.” This is exactly what has historically made it useful for cult programming, such as the LSD initiation rites of Aum Shinrikyo, who became infamous for terrorizing the Japanese subway system with sarin gas.

What causes people to upend their world with such fervency? It may be how psychedelics can make you so certain that you have learned something so profound, that must change your worldview, to a degree that is not earned nor healthy. As Dr. Johnson said, 100% of those involved in the clergy study wrote that they believed their psychedelic-induced experience was “strong or absolutely true.” This is not necessarily a good thing, he said, because, “There’s evidence that psychedelics make people more suggestible and you can kind of leverage them to having an overconfidence.”

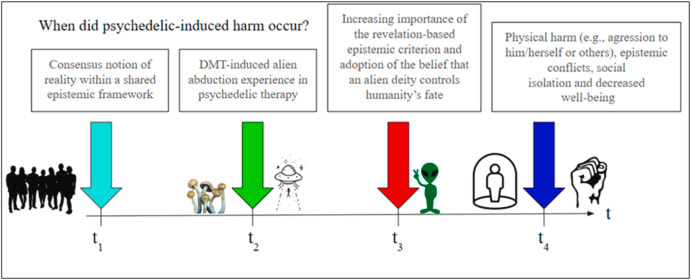

A recent paper on this phenomenon by researchers Lucas F. Borkel et al. points to what is called the “epistemic risk.” That is, psychedelics can not only change what you believe, but how you decide what’s true. Through an inflated sense of meaning, psychedelics can impact your truth filter and BS detector, the very ability to tell between truth and counterfeit. This may not only be bad for you, but for people who love you because of the decisions you then make with a broken discernment engine. Here is the researchers’ chart illustrating an example of how this can happen:

This issue has become harder to ignore thanks to a recent viral New York Times story of the also-a-psychedelic-billionaire Amy Griffin’s questionable “recovered memory” on MDMA, with consequences that may have inadvertently ruined an innocent man’s life. Another recent viral story of issues in IFS therapy—which has been used by many psychedelic therapists, including those leading psychedelic trials, and IFS’ founder promotes using IFS with MDMA therapy—presses the issue more of how psychedelic therapy can further impact our already eroded sense of reality in the AI era.

What has become obvious is that psychedelic sola experientia—faith in personal experience above all—is deeply misplaced. But this faith can be hard to let go of, like someone who feels the overwhelming presence of the Holy Spirit in worship services, only to wonder whether their faith had been built on a compelling series of musical chords to cover for something dark.

If this epistemic crisis remains looming over the entire field, we wouldn’t know it from the psychedelic industry. In a recent podcast by UC Berkeley about the study that further downplayed the issues, Pollan celebrated that the study produced a new “conversion.” The pilot flew.

Your Religion Patch is Ready for Download

If the Hopkins study revealed how spiritual experience can be engineered, other PSFC members show how it can scale. As the report notes, PSFC’s goals include “incorporat[ing] psychedelic experiences into well-established traditions” alongside a “long-term goal to accelerate the spread of psychedelic churches.”

PSFC member Steve Jurvetson, the billionaire long-time friend of Elon Musk on SpaceX’s board, posted glowing, glossed-over excerpts from Pollan’s article. “Pollan’s report reminds me of the mysteries of antiquity,” he said, highlighting one clergy’s report of “‘a spiritual orgasm.’”

Jurvetson’s sympathetic joy isn’t because he is a deep fan of religion. In March 2024, he tweeted some beliefs about children being raised religious:

“Indoctrinating children with the adult’s mind virus is cognitive child abuse. Few adults would chose [sic] their religion.” - @FutureJurvetson

In this case, if raising a child religious is “child abuse” to Jurvetson because it gives them a “mind virus,” it is apparently not a human rights abuse to experiment on religious people for a psychedelic gospel.

“Mind virus” isn’t a random term, but one that seems to have some coin in their friend group. Musk repeated it when he recently told Joe Rogan that buying Twitter wasn’t about money:

“The reason for acquiring Twitter is because it was causing destruction at a civilizational level…The woke mob essentially controlled Twitter. And they were pushing a nihilistic, anti-civilizational mind virus to the world. And you can see the results of that mind virus on the streets of San Francisco.”

To be fair, Musk himself joined the growing numbers of those expressing sympathetic views toward Christianity in the build-up to the 2024 presidential election, telling Jordan Peterson he’s “probably a cultural Christian” who believes “the teachings of Jesus are good and wise” and that Christian beliefs “result in the greatest happiness for humanity…I’m actually a big believer in the principles of Christianity. I think they’re very good.” This is a view of Christianity that mostly appreciates it for its utility.

However you may feel about woke mobs or Christianity, it seems our new soul engineers are not really looking to sell a product, but to fix what they see as one of many “mind viruses,” or perhaps merely misguided religions, through technological power, mining them for their moral value and updating them with psychedelic transcendence.

Does this mean everybody in the PSFC privately shares these views? No, but it’s like that hypothetical corrupt community land trust. If I’m giving to a project where key people involved really seem to believe in re-engineering religion, at some point, if I’m not saying anything against that and I’m still supporting them, then they do represent my views.

Now, nobody would argue that religious upbringings can be abusive. If someone views all religion as intrinsically brainwashing, that is their opinion. But if a proposed solution were to be drug-based counter-brainwashing with “mimetic countermeasures,” this would be, well, concerning.

Put this all on the middle rack and amplify it with Musk’s AI, and what comes out of the oven is a disturbing glimpse of the future where Jurvetson sees AI as psychedelic therapists, what he calls “the obvious long-term solution” due to labor costs. Perhaps the masses will get ShamanGrok and a pill while the privileged spring for artisanal ayahuasca.

If this seems like it may have downsides, it is a reminder that wealth becomes a force amplifier for any flaws in our epistemologies. This is an industry populated by people who have taken a lot of epistemology-shaking drugs, and the main truth they can agree on is that more people should take these drugs. Truth may be hard to come by, but the will to replicate overwhelms.

We already know that AI has significant issues with its ability to impact the judgment, beliefs, and behaviors of those who interface with it. Combine that with systematically adding drugs that twist our tools for discerning truth and are known for their ability to make one open to suggestion and persuasion, and you have what the report describes, “an elite circle [who] controls industries that work synergistically to shape perceptions of reality at scale.”

Combine that with a holy mission to enlighten the world, and you have the central pathology of the whole movement. For years before the PSFC existed, the Great Satan of the psychedelic subculture was public backlash against societal acceptance of drugs. In this mindset, the ignorant public mind is the ultimate scapegoat. This feeds a sacred duty to “teach” the masses, be they religion, the FDA, or the person who watches PBS. Since they cannot be expelled, they are transformed not into human partners in discerning truth, but into a target market, inoculated and engineered for their own good.

The Muraresku Surprise

But for all the grim outlooks, there is one public development that is fascinating and, as a “prisoner of hope,” I dare say is hopeful. Brian Muraresku’s book The Immortality Key expressed a vision of a legal psychedelic Reformation through Hopkins’ psychedelic studies, becoming a popular best-seller thanks to Joe Rogan. As Travis Kitchens previously reported, academics quoted in the book had begun to denounce it and its conclusions. What is now surprising is that while Muraresku may not discount the book, he has seemingly disavowed the whole psychedelic Reformation project.

As the report details, Muraresku was brought to Burning Man in 2023 by PSFC affiliates, where they set up a giant drone display with a meme from the book about psychedelic journeys, “Die before you die so that when you die you won’t die,” emblazoned across the desert sky. In the context of the phrase’s original inscription at St. Paul’s Monastery on Mount Athos, it is a Christian phrase. Out of that context and onto the playa, it is a Christian view stripped of Christ, seeing religion’s purpose as primarily about self-transcendence, self-preservation, and projecting of self-desire—which, okay, maybe still does describe many self-professed Christians.

But like I did with my views, Muraresku has also, to borrow from Pollan, “changed his mind” with some eye-popping statements:

“When reached for comment, Muraresku distanced himself from the project of mainstreaming psychedelics through any model. ‘I can think of no medical or religious institution, no psychedelic church, no Grateful Dead concert that will be able to deliver the kind of experience that literally takes centuries or millennia of iteration to perfect, and that has undeniably gone missing from Western civilization,’ Muraresku wrote.”

“On the subject of medical mainstreaming, he wrote of ‘warped incentives embedded into the for-profit pharma model ... racing to scale to maximize a bottom line. Simply put, money + psychedelics need to get divorced, and stay divorced.’ Regarding the religious use of psychedelics, he forecasted ‘a disaster down the road,’ citing ‘the warped incentives of recruiting and retaining members of a congregation,’ the ‘weaponization of mind-altering drugs,’ and the likelihood of cults developing. On ritual use, he wrote that ‘whatever genuine psychedelic rituals have been preserved by traditional cultures the world over, they ‘are best left uncorrupted by Western minds.’” Muraresku asked Psymposia to remind ‘“the psychedelic world”’ that I have never attended their conferences, and never will. And to please stop inviting me to conversations.’ He concluded his email by stating that he would like to ‘get the word out to everybody in the psychedelic community: ‘please leave me the fuck alone.’”

His sentiments are extremely relatable to me, and I will happily do so and wish him well. The disasters down the road, if realized, are truly harrowing to imagine. After once crossing paths in favor of combining psychedelics and Christianity, I am surprised to find myself saying that we have each reached a similar conclusion again.

We’ve Already Met

I think a question OK Computer never answered for my teenage self is how much we are to blame for our spiritual disease, how much is corporate, and how much is inevitable technological creep meeting our nature.

There is, then, one last risk that is just for me: I am at risk of being a Pharisee who gives thanks he’s not a psychedelic elite while caught in the same or worse spiritual dynamics. Maybe I’m just trading one form of seduction for another, reenacting spiritual superiority in Christian clothes, convicted that my new even deeper experiences revealed a truth others are missing, and I need to share a message to help. What’s different? Maybe not much. I can at least say that I think that is true that Christ was who he said he was, and the implications of that have changed everything for me. What I can also say is that Christianity teaches me I’m a sinner in need of grace, while psychedelics taught me we are gods who can make ourselves in our own image. If both are dangerous when amplified by power, only one tells me to divest of glory-seeking. So watching certainty combine with wealth and technological power to reshape souls gives me fear, not because I’ve transcended these human dynamics into a new Christian enlightenment, but because I know how powerful they are.

So it’s really hard for me not to feel the heaviness of the possibilities here in a world that does not need more bad news. I know good has and will come out of it, but I still mourn those who will be hurt and will not recover because of the hubris of those involved. Minds, families, and souls have already been left on the cutting-room floor of the billionaires’ cultural editing room.

For a long time now, a big question for me has been about the implications of how these drugs subtly and less subtly shape minds. As a pastor, I am particularly concerned with how the rollout of psychedelic therapy seems to be explicitly targeting “converting” people. This should give people who don’t like Christians pause, too, because we know Christians can and will use the same means to convert people to their version of a psychedelic gospel, and that will also be deeply wrong and disturbing. So again, not just for Christians but for anyone seeking care, you have to be diligent in wondering: who is shaping this environment? What are their underlying beliefs? What are their ethics, and how do they respond to harm or not? What are the implicit, silent values filtering through in unconscious ways? And as all Christians must ask ourselves of our churches, are the values shaped by the gospel of Jesus Christ, or just his aesthetics?

None of this denies any legitimate benefits people may have gotten from psychedelics. I still believe better science will yield medical treatments using them, perhaps over generations and disassociated from this movement, just as we no longer eat Seventh-day Adventist cereal. But I think the soul engineers are wildly over-optimistic about our ability to spiritually fix ourselves. And I think this is a case study of how sin begets more sin. My sin doesn’t like that Luke 18:9-14 teaches that we are farther from God when we are right but arrogant than we are wrong and feel how wrong we are. I hope I am wrong about all this, not only so that disaster can be avoided, but that I can be humbled again to be closer to God than my confirmation bias pride. I am still afraid I will be right, and the consequences of being right would be a world not only with the consequences themselves, but a kneecapped societal ability to self-correct when more and more people share psychedelic-induced grandiosities that buy a misguided loyalty to these drugs.

How long the PSFC exists in its current form remains to be seen. It is just one form of a problem that will re-emerge wherever psychedelics and money congeal. Like any nonprofit, the PSFC’s donors are the first and primary customers of PSFC projects, the story it sells itself about what it’s doing. If anyone feels caught up in this, I would say that if Muraresku has permission to reject the prompt, so do you.

I want to return to the message Elon’s friends cast across the sky and why it’s almost right. To “die before you die so that when you die you won’t die” with Christ vacuumed out defeats its Christian purpose: to be in Christ. “If we died in Christ, we will live in him” is crucial to the gospel (Romans 6:8). But dying to the old self isn’t worth anything if the “new self” is clothed with LLM-generated aesthetics, imbued with the power of simulated profundity, a vacant “meaning” for the sake of having it, a gravitational pull into a dark star. I do get why we shouldn’t throw around the word “demonic.” We should be judicious and fair. Just like the first Hopkins psilocybin experiment was careful not to say these were “mystical” experiences, but “mystical-type” experiences, maybe this isn’t demonic, it’s just demonic-type.

As I was processing all this, I’ve come to what might be some unlikely common ground. It is not only a billionaire who thinks religion is a mind-virus. Christianity, itself, believes that worshipping religion is also a “mind virus” which Christ liberates us from. Religion scapegoats us. Christ stands opposed to religion, but in paradox, still calls us to be gathered in his body, an ecclesia, a called-forth-and-sent-out assembly, a Church. We Christians still believe that ordering this body must regrettably result in some kind of religion, intentionally cultivated, a necessary technology to mitigate sin, but also a sign of sin itself. We use revealed religion in the patterns and liturgies of the Church as a gift from God to regularly remember together the fullness of who He is, lest we worship something else while fooling ourselves into thinking we don’t have religion just because we aren’t in church. We are all sinners, and so we all have religion, chicken and egg.

The problem is in the project to patch the mind virus. A few billionaires are just the most powerful and well-funded expression of a therapeutic-technological worldview that is already endemic to the entire psychedelic-spiritual scene. But actually, I believe we are all in this picture, and we shouldn’t like it.

If we want to meet the soul engineers, we must meet ourselves. We all try to be soul engineers. We try to earn grace. We want a technique to fix us, or at least the occasional rave to ward off the madness. We religious people want prayer practices and worship services to get us feeling right rather than something we are called to do in response to grace while caring for the poor and the downtrodden. We want our politics to make us holy before God and to repair the national spiritual deficit ourselves. And we want it with drugs of all kinds. However effective that is for some in the great spiritual casino of the psychedelic industry, it is also a dangerous and particularly jacked-up way to do it, considering the ramifications on the mind and human agency. Our soul engineering wants to be baptized in power and sacrifice outcasts who diminish our self-image and threaten our goals. The gospel scandalizes our efforts by taking on sacrifice until it redeems the outcast through weakness. And in this world, we are all living in exile.

To be in Christ, if only for moments, if only partially, if only to succumb back again to The Machine, is to experience freedom from anyone’s soul engineering, especially our own, to see visible signs of the invisible God leading us away from a parade of false images. For Christians, to be home wherever we are is to be in Christ. When those of us who call him Lord do so, it is to say he is sovereign over our worst instincts, even as we hand ourselves, the jailer, the keys right back, trusting and believing that it somehow matters to know that we are called for more than this and less of this, and we do not need it.

I am a Presbyterian pastor in northern Vermont. You can reach me at revjoewelker@gmail.com for thoughts, factual corrections, and prayers.