Publish or Perish

Despite failing human subjects protections, a Johns Hopkins psychedelic clergy study driven to influence the public appears set to be published.

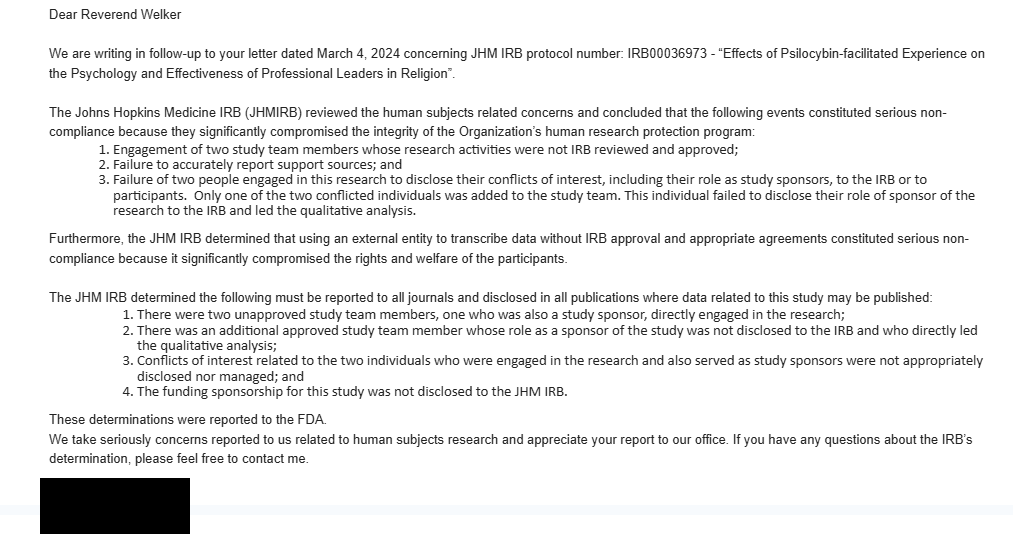

Those following the Johns Hopkins and NYU psychedelic clergy study via this newsletter know that about six weeks ago, I received word that the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) found that the study had multiple counts of serious non-compliance with the university’s federally-required human subject protections.

Despite this, it appears the study is set to be published by a relatively new psychedelic journal with many ties to industry insiders (more on that below).

Before the findings dropped, Michael Pollan also sent me written questions for an upcoming piece about the study for The New Yorker. Given Pollan raised the psychedelic tide by promoting Johns Hopkins’ psychedelic research, and given that he seems to have a passion for protecting psychedelics’ public image from “negative stories,” and given that he is a colleague of Bob Jesse’s (who is the founder of study sponsor Council on Spiritual Practices), and given that some improper donor involvement was at the heart of the non-compliance, and given that he has even publicly discussed PR strategy with Bob Jesse, it should at least be interesting to see what The New Yorker publishes.

I had hoped to post more detailed thoughts on the Hopkins IRB response earlier, but Easter season kicked in along with a slew of threads converging. So what can we make of the findings?

Breaking Down the Findings

As reported, Johns Hopkins Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the engagement of unapproved study team members, undisclosed sponsor roles of study personnel, and the involvement of unapproved donors were part of multiple counts of “serious non-compliance” that “significantly compromised the integrity of the Organization’s human research protection program,” with an unauthorized use of a transcription service that “significantly compromised the rights and welfare of the participants.” JHU said these have been reported to the FDA. Hopkins’ Office of Human Subjects Research referred my follow-up questions to the Johns Hopkins Medicine Media Relations office, who did not return requests for comment. I cannot independently confirm if the NYU IRB also investigated. I sent the findings to the NYU IRB with an additional letter, but they did not say whether they had previously investigated, and it is likely standard practice to not say.

Since most of us don’t know much about IRBs and may have just heard that acronym for the first time, how do we put this in context?

So, uh, what is an IRB?

I’m going to give my best non-scientist’s explanation of an Institutional Review Board (IRB) based on my experience familiarizing myself in this process (here’s also just a link to the Wikipedia article for the lazy but more thorough education). I bring you the power of Google-fu, my learning experiences over the past couple years, and AI deep research tools to double-check my work (hey, I’m just fully disclosing that, vet it for yourself):

Human research done in the United States is regulated by the US Department of Health and Human Services, but they farm out most of the actual regulating to the sites. Each institution doing human research is required to maintain an IRB to do the actual regulating. While IRBs have minimum standards of how they must operate according to federal regulations, they don’t all have uniform policies; Johns Hopkins’ IRB does not necessarily act the same as, say, the University of Vermont.

The primary thing all IRBs are charged to do is protect the rights and welfare of people who sign up to be researched on. Okay, still vague. More specifically, the IRB’s main power is to approve and disapprove research proposals to check (among other things) for ethics, safety, and informed consent in the study design. They also approve research staff and donation sources, engage in periodic reviews while the study is going, and in this case, conduct reviews/audits/investigations after the fact if issues are raised.

So when people say an “IRB investigated,” it does not mean they looked into every possible ethical dilemma or research malpractice. It does not mean that they have any kind of subpoena power (they don’t). They may only conduct interviews if they feel necessary (I was not interviewed). When investigating, they seem to mainly review whether proper paperwork like informed consent documents were filed, whether things like adverse events were properly reported, and yes, whether sponsors and study team members were properly disclosed, vetted, and trained. Contrary to what may be assumed, they usually don’t investigate research misconduct like data fraud, which is often handled by other university departments like the Johns Hopkins Office of Research Integrity.

How do we measure the response?

For one, it seems to be unusual that they respond at all, so kudos to Hopkins for that. As one university bioethicist not in psychedelic research told me, “I'm kind of amazed that the Hopkins IRB did anything at all, and even more amazed that they told you about it. That would never happen here [at my university]. As far as what they didn't do goes: most investigations like this stick really close to the federal regulations, so if the issue is something really out of the box, ethically speaking, they will usually play it safe and say nothing. Also, it's worth remembering that IRBs don't really have much power. The university can take disciplinary action—and the FDA can, of course—but the authority of the IRB (at least as far as I know) extends only to the protocols they review.”

So there is still a lot unknown and the IRB won’t say, including the identity of donors and researchers who were in non-compliance.

But “serious non-compliance” is a significant and formal term, not an arbitrary adjective or minor administrative error. Take, for instance, UC Merced’s definition, which lists it as the highest level of non-compliance, describing it as that which “has a significant adverse impact either on the rights or welfare of participants or on the integrity of the study data.” Serious non-compliance often refers to actions that involve a deliberate disregard for the regulations or the IRB's directives. That the JHM IRB determined the study’s actions "significantly compromised the integrity of the Organization’s human research protection program" is as strong an indictment as it sounds.

Some of these findings are confusing at first because of the overlapping roles. To break down the specifics of what they found a bit more and remix it into layman’s terms:

1. “Engagement of two study team members whose research activities were not IRB reviewed and approved;”

There were two people directly involved on the study team itself whose study actions did not go through the proper oversight. This could mean the IRB didn’t get a chance to vet them and evaluate whether they were qualified to serve on the study team or train them on the IRB’s expected ethical practices.

2. “Failure to accurately report support sources;”

Funding for the study was not fully disclosed for proper oversight. This means the IRB did not get a chance to assess the bias and conflicts of interest of donors that would be influencing the study design. Participants also have a right to know who is funding the research they are signing up for. Would IRB approval have been given if they were aware of support sources and their motivations? Would all participants have signed up?

3. “Failure of two people engaged in this research to disclose their conflicts of interest, including their role as study sponsors, to the IRB or to participants. Only one of the two conflicted individuals was added to the study team. This individual failed to disclose their role of sponsor of the research to the IRB and led the qualitative analysis.”

Hopkins regulators were unaware two people involved were donors or their conflicts of interest. One person directly led parts of the research—they were approved to the team, but their status as funder was not disclosed. The other person was “engaged in this research” while apparently not on the study team, and also was unknown to regulators that they were a donor.

The required disclosure, “conflicts of interest…were not appropriately disclosed nor managed,” appears to be a bit of an understatement; one sponsor also funded participants to advocate for psychedelics in their religious communities and funded a retreat between participants and researchers, as reported in the New York Times.1 Some additional background on the researchers was reported by Reason.2

Combined with point 1, and looking at the IRB’s required disclosures, it seems there were three people in question who were “engaged in the research” without proper authorization—two of which were on the study team without approval,3 two of which the IRB didn’t know were funders, and one was both. So it looks like:

Study Team Member A (unapproved to study team, not a donor)

Study Team Member B (unapproved to study team, also an undisclosed donor)

Study Team Member C (approved to study team, but status as donor wasn’t disclosed, led the qualitative analysis)

Since the IRB says participants weren't fully aware of the potential biases influencing the study, the failure to disclose these critical conflicts of interest and roles appears to have compromised the ability for participants to provide fully informed consent.

4. “Furthermore, the JHM IRB determined that using an external entity to transcribe data without IRB approval”

By using an external transcription service, the study compromised participant confidentiality and privacy. A third-party that Johns Hopkins’ IRB didn’t know about had access to participant interviews outside the oversight of the IRB.

So while the information the IRB disclosed is limited, the findings are still especially concerning given several donors and researchers were motivated to influence public opinion to embrace psychedelics.

Beyond the IRB’s commentary is the remarkable fact that this occurred under the study’s principal investigator, legendary researcher Roland Griffiths. Because of how he opened doors for psychedelic research, Griffiths’ legend had grown in sync with the psychedelic field’s. In particular, Griffiths’ reputation of integrity and attention to detail lent much-needed credibility to psychedelic research.

In June 2023, alongside a long line of NYU and Hopkins researchers, Michael Pollan introduced Griffiths to a dinner in his honor in front of ten thousand psychonauts in this way:

I've interviewed a great many scientists but none of them is remotely like Roland Griffiths. Why? I think it's because he is a man of two minds. Two equally interesting minds. One as you've heard a lot about, is the mind of a rigorous, scrupulous, well-respected scientist, so what he says carries the weight of Science with a capital S. I interview lots of people like that and I harvest their quotes in my articles. But the other is the mind of a man willing to say things about consciousness, about ultimate reality, about the fate of the species that will absolutely blow your mind. Honestly, for a journalist, Roland is a dream come true…This is who we have before us: a first rate intelligence consisting in equal parts of rigorous scientist and equally rigorous spiritual explorer, able to hold not just two ideas, but two entire worldviews in one mind. I think I speak for all of us in saying that our minds have been immeasurably expanded by sharing this life with his.4 5

As director of the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine, Dr. Michael P. Bogenschutz, said at the same dinner, “He was the most meticulous scientist I know, and I can’t imagine him ever knowingly saying anything that was untrue.”6 Griffiths bequeathed a professorship bearing his name before his death in October 2023.

But it seems unlikely that someone of Griffiths’ experience made these mistakes unintentionally, especially his failure to disclose to university officials that a donor was directly leading qualitative analysis. I asked several researchers and bioethicists who are not in psychedelic research about this, and they said while donors often have input in the design of a study and giving feedback on results, this level of direct involvement with subjects in a drug study is something they hadn’t seen before. I couldn’t find other examples of this in my research, but I welcome someone giving an example.

What the IRB Findings Don’t Say

As discussed, IRBs have a limited investigative scope and even more limited appetite for communication beyond legal requirements. There is much they can’t and won’t say.

Behind their opacity, the IRB’s conclusions are not a “clean bill of health” for the rest of the actions around the study. Hopkins will likely not disclose the evidence weighed or other concerning behavior beyond their scope and policies. In response to emailed questions, Hopkins did not say whether there was any internal discipline for the researchers, donors, or the Hopkins Center for Psychedelics and Consciousness Research, nor if there will be increased oversight for psychedelic studies going forward.

The IRB was ironically, if predictably, silent on the original cause of the investigation. I blew the whistle on the study after being disturbed by my experiences at a Christian non-profit spawned from the study and then realizing its founder had been publicly describing what would have been a boundary-violating “ordination” experience in his session by a study guide. According to multiple sources, video reviews showed that this event didn’t happen, and the participant now ascribes the story to a faulty memory. Things still don’t make sense to me: why did it take so long to investigate, and when was he informed that it didn’t happen? If it was properly investigated in time, why did a donor-researcher keep paying him to run the Christian non-profit while telling the story? In following up with the IRB, they of course would not divulge any more details about what they found about this event.

The IRB was also predictably silent about specific concerns around donors’ and researchers’ religious and spiritual agendas, and concerning behavior of researchers, donors, and participants that wasn’t officially part of research activities. For one instance, a participant went on a peyote retreat with a study team member. Did this fall under “conflicts of interest were not appropriately disclosed nor managed”?

So the IRB’s findings are silent on the bigger picture issues. I expect many will be frustrated by this report by what it doesn’t say, and what Johns Hopkins is unlikely to ever say. Without legal requirements, the public may never know the full story.

Why “Serious” Findings Are Serious

To be sure, this situation was not like, say, the Walton Family Foundation didn’t get permission to interview rural teachers about how they taught third grade. This involved giving humans drugs known for inducing openness to suggestion by people who have spent decades advancing psychedelic spiritual and religious goals. With drugs known to create culty group dynamics and utopian visions, a donor acting as researcher funded multiple participants to start non-profits geared towards their religious audiences, and a significant amount of participants made psychedelics a key part of their theology and pivoted their careers. What may seem like proof of spiritual validity to one looks like a red flag of undue influence to another.

Some in the psychedelic movement are privately spinning the primary finding of the IRB as having “cleared it to publish,” but taking this as the primary takeaway signals a continued lack of seriousness about ethics that surrounded the study and the broader psychedelic movement for years. As PsychedelicWeek said on X/Twitter, “The federal protections referenced stem from the Nuremberg Code and atrocities such as Nazi torture of people in concentration camps and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. So, we should take research ethics seriously & defend the rules intended to protect human research participants.”

These were not small lapses in paperwork, but behavior that warrants questions as to why it was hidden from regulators.

Silence and Hidden Donors from JHU

Johns Hopkins Medicine and JHU’s Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research (CPCR) did not return requests for comment on the findings. I have yet to see a public acknowledgment from either, and I don’t expect to.

While Hopkins remains silent on this issue, the CPCR shared an interview with the first recipient of the Griffiths Professorship, Dr. David Yaden, on “Psychedelics Research: Evidenced-Based Messaging, Informed Consent, and Adverse Events Surveillance”. Dr. Yaden has published extensively on psychedelic ethics. Within the interview, Dr. Yaden made the contested claim that “psychedelics do not pose unique challenges to informed consent,” a view many others disagree with in the field (a deeper dive for another day). Dr. Yaden went on to say this was because “there are plenty of other medical interventions that involve potentially major changes to function and identity — so psychedelics are not exceptional in this regard. But psychedelics do have a set of features that makes them distinct and are, therefore, worth substantial consideration.” Dr. Yaden also indicated they are partnering with the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics to improve their consent documents and called for better adverse event reporting.

Dr. Yaden did not return a request for comment on the IRB findings of serious non-compliance that happened under Griffiths.

Beyond silence, sometime in the past year donors to the Griffiths Professorship Fund were hidden from their website. Here is an archived page from June 2024 with a list that includes one of Elon Musk’s closest allies and D.O.G.E. friend Antonio Gracias, Elon Musk’s sister-in-law Christiana, Sam Harris’ foundation, and Tim Ferriss.

Most relevant to the religious professionals study:

Riverstyx (whose co-director was on the study team) was listed as a donor at the “Partner” level, which according to JHU’s giving website for the fund, indicates a gift between $250k to $999,999.

Claudia Turnbull, reported as a guide on the study,7 was listed at the “Visionary” level of gifts over $1M, and was described with special thanks: “Claudia Turnbull, whose leadership brought together the needed funding.”

Michael Pollan was also listed with Judith Belzer as “Supporter” donors with gifts between $1,000 - $99,999.

Some Organizations

While the IRB will not disclose the identities of the unapproved donors and researchers, and I cannot confirm, it is worth sharing a few organizations that are known to be related to this research to get greater context. I hope the published paper(s) will bring more clarity. I previously covered at more length some of the additional connections and backgrounds of people connected to the study here, here, and here.

Note: To be clear, some people below may have been properly reported to the IRB, and I don’t want to engage in speculation (okay, I know someone reading laughed at that). One of the organizations below appears to not even be a sponsor, though still significantly tied to the study. Have I given enough disclaimers to avoid empty legal threats again?

Riverstyx Foundation

The goal was to “give clergy the opportunity to connect deeply with a sense of spirit, of the divine” and, ideally, to reinvigorate “the spiritual foundation of our society with more meaning.”8

Lucid News on T. Cody Swift, Co-Director, Riverstyx Foundation

Based on all available evidence, it appears Riverstyx Foundation’s T. Cody Swift donated to the study while leading the qualitative analysis without his sponsor status disclosed to the IRB under the oversight of Roland Griffiths. Riverstyx is known to have funded the study, and Riverstyx has given millions of dollars to Hopkins research over the years, with Swift getting access on Hopkins’ study teams before, including as session monitor.

Swift was the presenter of the qualitative findings when the study was presented at a conference in 2023, where he said he conducted all interviews alongside Dr. Alexander Belser of NYU. It is unclear if he co-led qualitative analysis with Dr. Belser or if it was led by another donor I am unaware of, but I could find no evidence Dr. Belser donated to the study.9 The New York Times reported, “Swift said that his foundation provided financial disclosures in published papers and on its website. ‘I always try to hold awareness of how my personal views might influence the people I work with.’” However, this does not speak to if his disclosures were given to the IRB.

Riverstyx also funded participants in the starting of non-profits aimed at religious audiences. An additional Riverstyx employee at the time was engaged in the research and sat on the board of the Christian non-profit funded by Riverstyx.

Riverstyx’s funding priorities have included many donations towards religious psychedelic causes and have stated a desire to influence public attitudes. Per their website, they are focused on “social transformation” and “high-leverage social change” in hopes of “effectuating enduring change in both cultural awareness and social policy,” elaborating:

“Riverstyx attends to the places in society and our psychology which have been relegated to the shadows- out of fear, ignorance, and puritan influence- recognizing that which is repressed only festers and breeds pathology in its unnatural separation.”

Council on Spiritual Practices

“The challenge for all of us: find, or create, or improve, or be reformers within social contexts that provide day-in, day-out, weekly support for the shared enterprise of living out what a primary experience offers to us…Let’s learn to make peace with [religion]. It’s out there. Not only is it out there, but the world’s finest land, and architecture, music and so on have all been devoted to this enterprise. Wouldn’t it be interesting if it became more potent at delivering on its own promise of helping people be kinder to each other?”

Bob Jesse, Council on Spiritual Practices, 200910

Bob Jesse’s Council on Spiritual Practices has been repeatedly listed as study sponsor in many places. While Jesse is closely tied to the study team, I could not find evidence that Jesse was directly engaged in the research or part of the study team. Via CSP, founded in 1993, Jesse has been strategizing research for psychedelic spiritual and religious goals since his involvement in the San Francisco rave scene through the 1990s.

Michael Pollan’s book profiled part of how he organized the earliest Johns Hopkins psychedelic research and has acted as a kind of psychedelic sage to a once-tiny research community. Jesse has spent decades talking about psychedelics being combined with religion, including about his views as psychedelic experiences as a “new kind of doctrine” and a “birthright.”11 He also wrote a brief for the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005 in support of an ayahuasca group’s religious freedom.

Jesse is now a colleague of Pollan’s at the UC Berkeley psychedelic center that Pollan co-founded. According to Pollan in 2023, Jesse reads every issue of UC Berkeley’s industry newsletter The Microdose to make editorial suggestions for any exaggerated or misrepresented language.12 Thus far, The Microdose has not reported on the findings of serious non-compliance with the study.

Heffter Research Institute

“What happens when you can offer someone an experience of awe? How does that change your life?”

Claudia Turnbull, study guide, board member of Heffter Institute13

Heffter Research Institute is one of the oldest and most significant psychedelic funding bodies, a mainstay of the psychedelic vanguard since its founding in 1993. In Heffter's 2023 newsletter, they claimed to have funded 156 studies. It appears it did not sponsor the religious leaders study, but there are still significant other ties.14 I did not previously report on Heffter in my original series of posts on the study.

Since the IRB’s findings, I was made aware that Heffter had several significant connections to the study team and donors, and some are a bit strange; I have now been told through a third-party that Heffter did not sponsor the study,15 but they had claimed to have sponsored it when the study launched back in 2015, deleting the post that had been up for ten years after I asked earlier this week. Their website claimed this yesterday (emphasis added): “Our researchers are also collaborating with the Council on Spiritual Practices to explore the effects of psilocybin with religious professionals to understand how a mystical-type experience may benefit their work as clergy.” As I was double-checking links, I saw this had changed to clarify: “Researchers Heffter has supported at Johns Hopkins and NYU also collaborated with the Council on Spiritual Practices…” The study is currently listed as “Current Research” in their Spirituality section, with the now-added note: “Note: Heffter Research Institute did not provide funding for the Religious Leaders Study.”

Heffter’s page on “Future Research” also adds more context for their relationship to the study trial sites: “The founding of the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic Research, the NYU Center for Psychedelic Medicine, and the initiation of the Usona Institute project to achieve FDA approval of psilocybin for medical treatment, are deeply gratifying to everyone at Heffter, having been instrumental in mentoring and funding the work that led up to those profound institutional developments.”

Claudia Turnbull is currently listed as a Heffter board member, along with her husband Carey, and reportedly acted as a study guide.16 It was also reported in Lucid News that the Turnbulls donated to the study. Turnbull also is listed on the advisory board of NYU’s psychedelic center (which ran the other trial site), where Heffter has donated, and was listed as a $1M donor to the Griffiths professorship as detailed above. Turnbull received an M.A. in Consciousness studies from Goddard College in Vermont, not too far from me. Goddard sadly recently closed due to financial struggles facing many small liberal arts schools and is known for producing my favorite band Phish (who I would argue are also scholars of consciousness).

T. Cody Swift of Riverstyx also regularly donates to Heffter, is also listed as a Heffter board member, and is also listed on the advisory board of NYU’s psychedelic center.

The study's principal investigators Dr. Griffiths (Hopkins) and Dr. Stephen Ross (NYU) were also listed as board members of Heffter in 2015 when the study commenced.

Psychedelic Medicine and Study Connections

Before the digital ink had scarcely dried on the pixels of the IRB’s findings, the study was apparently accepted by the two-year old journal Psychedelic Medicine. The journal has considerable connections to Hopkins and Heffter:

Dr. Charles Nichols, listed as a board member of Heffter and Co-Editor-In-Chief. Riverstyx’s site indicates it has donated directly to Dr. Charles Nichols’ research in 2021 and 2025.

Former Editorial Board member Dr. Roland Griffiths of Hopkins, deceased, study's principal investigator, still also listed board member of Heffter

Associate Editor Dr. Albert Garcia-Romeu of Johns Hopkins, also Associate Director of the Hopkins psychedelic center

Editorial Board member Dr. Fred Barrett of Johns Hopkins, also Director of the Hopkins psychedelic center

Editorial Board member Dr. Charles Grob, co-founder of Heffter

Editorial Board member Dr. David Nichols, founder and Vice-President of Heffter

Editorial Board member Dr. Katrin Preller, listed as Chief Scientist of Heffter

Co-Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter Hendricks has previously received funding from Heffter for his research.

An article authored in March 2023 indicates that the two co-editors met at the board meeting of Heffter in 2015.

In requests for comment on the concerns I had around Psychedelic Medicine’s conflicts of interest, editorial independence, peer-review process, transparency, and accountibility while asking about Heffter’s sponsorship of the study, I received the following from Co-Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter Hendricks: “Heffter Research Institute did not sponsor the study. I served as the EIC of the manuscript and have never received funding from any of the study’s funders. The study was subjected to peer review and no one from JHU or NYU was involved in the editorial process, including those on the editorial board.”

How weird is all this? I come away with the feeling like the lines are completely blurred and arbitrary all over the place here, with extensive social ties and pressures that could easily compromise judgment. Not to mention large swaths of the psychedelic industry are part and parcel with a social movement of activist research and wellness influencers with a side of therapy cult. But maybe it’s all normal.

Some have argued to me that criticizing this study based on the motivations is the “genetic fallacy” rather than looking at the data itself (the “genetic fallacy” is criticizing something on its origins rather than the contents). Why not publish and let people evaluate it? Setting aside ethical considerations, I think there are two issues with this. For one, the “why” isn’t just about the “why,” it’s how the “why” affects the “how”; data collection and analysis were directly shaped with a level of unapproved sponsor involvement that is potentially unprecedented in drug research, and it’s unprecedented for good reason. The potential for biased data through how questions are asked and interpreted is not just about the donor motivations in and of themselves, it's about the integrity of the research process in data creation and collection.

The second problem has to do with the harms of bad science communication that are extremely predictable here. Nobody knows better than psychedelic researchers that the public goes on vibes and headlines rather than specifics. Several people involved have demonstrated they can’t be trusted to responsibly communicate the information; people have already been using this unpublished study to advance psychedelic narratives and careers for years, and people have already been harmed by that. Even in presenting the study’s preliminary findings in June 2023, Griffiths expressed concern about catastrophic harm from too much cultural uptake of psychedelics.

There are times when it feels to me like there’s a vertically-integrated monopoly in the psychedelic scientific apparatus. In psychedelic research as a whole, the donors are the researchers are the journal editors, all existing in overall alignment with psychedelic industry media and an overwhelmingly sympathetic mainstream media. This is not even to mention the extra complications when participants “go pro” in psychedelics and exist as colleagues with the same donors and researchers found to have committed ethical violations but who now share incentives. And then there are the normal pressures like “publish or perish” and quotidian corruption in scientific research writ large.

Whatever scientific use may come of the study environment—and I do like to remember that the Seventh Day Adventists still gave us all cereal and vegetarianism—it seems like the scientific findings have never been the main point. There is a story to tell and sell.

Core Concerns

So there are many egregious factors that bear on concerns around the dissemination of this study and about the well-being of the participants and public. These participants were given high-suggestibility drugs known for their abuse potential by psychedelic guides. These drugs were administered to clergy by a score of people who have openly stated goals to influence religious traditions to embrace psychedelics. Donors funded participants to promote psychedelic usage among religious populations and others have publicly indicated goals of influencing public policy and religious attitudes around psychedelics, and previous researchers at Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelics and Consciousness Research (CPCR) have publicly expressed concern about the environment at the CPCR.

In any case, once again it was proven that it’s better ask for forgiveness than permission. Whether Griffiths knew he was taking a gambit or not is a question, but it paid off: in the end, the Hopkins IRB’s findings were serious and necessitate disclosure, but they look like they will still get some papers and press.

Given the legend of Griffiths at Hopkins, there is good reason to wonder if there are other reasons why, after all these counts of serious non-compliance and the greater context, the IRB still permitted the use of data to be published. And given that the agendas of sponsor organizations have included influencing public opinion by instrumentalizing scientific research, and that these drugs are known to cause belief changes influenced by their environment and the participants’ livelihood was directly connected to their belief systems, there continues to be more serious issues beyond the plain text of the IRB’s response letter. The study was, in my view, abusive to the principles of scientific research and the human beings under Johns Hopkins’ care.

The core of my concerns remains unchanged: I believe the evidence overwhelmingly shows that this study experimented on human beings for an evangelical mission to influence the public to embrace psychedelics, an agenda manifestly more important than its stated scientific purpose or following required ethical practices. I don’t know if the IRB could have responded more strongly and what they have done behind the scenes. But I urge all IRBs who oversee psychedelic research to review their policies to ensure something like this never happens again, with institutional leadership making that commitment clear.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/21/health/psychedelics-roland-griffiths-johns-hopkins.html

https://reason.com/2025/02/09/the-most-controversial-paper-in-the-history-of-psychedelic-research-may-never-see-the-light-of-day/

Earlier version was lacking “without approval,” added for clarity on 5/10/25

youtube.com/watch?v=QOfyZtoU_o8 , timestamp 1:06:10

An earlier version of this generated transcript incorrectly capitalized “consciousness” and “ultimate reality,” fixed on 5/10/25

youtube.com/watch?v=QOfyZtoU_o8 , timestamp 28:15

https://www.lucid.news/carey-turnbull-donor-investor/

https://www.lucid.news/psychedelic-philanthropist-blazes-path-psychedelic-future/

Dr. Belser’s biography in published journals has read “He is also helping conduct a qualitative study of religious leaders who are administered psilocybin,” but I could not find any information indicating Dr. Belser has donated to the study.

Bob Jesse, “Horizons 2009: Bob Jesse ‘Entheogens, Awakening, and Spiritual Development’,” youtube.com/watch?v=IC52wtLjZtM , timestamp 13:45 and 29:00

youtube.com/watch?v=lM-yinhpOgQ , timestamp 17:30 for “doctrine,” youtube.com/watch?v=HZQEISKoTYk at 3:20 for “birthright”

https://2023.psychedelicscience.org/sessions/tempering-psychedelics-a-conversation-with-michael-pollan-and-bob-jesse/, timestamp 18:45

https://www.lucid.news/carey-turnbull-donor-investor/

Original phrasing said “did not officially sponsor,” I removed “officially” as a potentially misleading adjective on 5/10/25

Dr. Charles Nichols of Heffter did not directly respond to comment when I asked him and fellow Co-Editor-In-Chief of Psychedelic Medicine Dr. Hendricks.

https://www.lucid.news/carey-turnbull-donor-investor/